QUICK SUMMARY

The unjust imprisonment of Doña Teodora Alonso — José Rizal’s mother — was one of the defining traumas of his early life. Her suffering revealed to him the cruelty of colonial justice and planted the seeds of his lifelong struggle against oppression. This event transformed his childhood innocence into sharpened moral awareness and shaped the reformist fire that later ignited his writings.

A Mother’s Integrity in a Time of Colonial Abuse

Doña Teodora Alonso was known throughout Calamba as an educated, principled, and compassionate woman. She came from the respected Alonso and Quintos families, both known for scholarship and public service. Her reputation for intelligence and moral strength made her a central figure in Rizal’s upbringing.

Yet even a woman of her standing was not safe from the abuses of colonial authority. In 1871, when José Rizal was barely ten years old, Teodora became the victim of a malicious accusation that would cast a long shadow over the family.

The False Accusation and the Unjust Arrest

The incident began with a family dispute between Teodora’s half-brother, José Alberto, and his wife. Rumors spread that Alberto’s wife was unfaithful, and Alberto sought reconciliation with Teodora’s help. Instead of appreciating her efforts, the wife accused Teodora of poisoning her — a charge that the local Spanish authorities eagerly embraced without evidence.

Colonial officials seized the opportunity to humiliate the influential Mercado-Alonso family. They ordered Teodora’s arrest in a manner designed to break her spirit. She was forced to walk from Calamba to Santa Cruz, Laguna — more than 40 kilometers — under guard. Witnesses said she remained composed, refusing to show fear despite the humiliation.

Her wrongful imprisonment lasted almost two and a half years, marked by constant appeals, legal maneuvering, and the refusal of friars and local officials to acknowledge clear injustice. The experience exposed the brutal reality that law in the colony could be twisted by prejudice, corruption, and personal vendetta.

The Boy Who Watched Injustice Unfold

For young José Rizal, the imprisonment of his mother was a shattering moment. Teodora had been his first teacher, the source of his love for learning, language, and imagination. To see her dragged away in chains — innocent, dignified, and suffering — became his earliest lesson in colonial cruelty.

This event awakened in him several convictions that would remain central throughout his life:

First, that power without accountability becomes tyranny. He saw how officials used their authority to terrorize the innocent.

Second, that justice in the Philippines was not blind — it was weaponized against Filipinos.

Third, that silence in the face of injustice was impossible for anyone with conscience.

Rizal later wrote that his mother’s wrongful imprisonment planted the seeds of his hatred for tyranny and his desire to lift the moral and intellectual life of his people.

The boy who once sketched and wrote poems in innocence began to understand the darker forces shaping his country.

Family Hardship and Collective Resolve

While Teodora was imprisoned, the Mercado family faced economic and emotional strain. Her absence meant the loss of a stabilizing force at home, especially for her many children. Don Francisco worked tirelessly to secure her release, spending money on legal petitions, traveling long distances to appeal to authorities, and enduring the scorn of friars who wanted the family humbled.

Despite this hardship, the family did not break. Instead, they grew more united, more alert to injustice, and more determined to give their children an education that would empower them to resist oppression.

This collective suffering forged in Rizal a deep sense of familial loyalty and an understanding that personal hardship can become a force for national awakening.

The Wider Message: When a Mother Suffers, a People Suffer

Doña Teodora’s imprisonment symbolized what thousands of Filipinos experienced under the colonial system. Many innocents languished in jails because of capricious accusations, clerical manipulation, or local rivalries. The case laid bare how the colonial justice system protected the powerful while crushing the vulnerable.

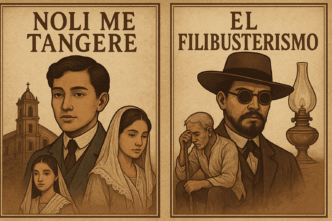

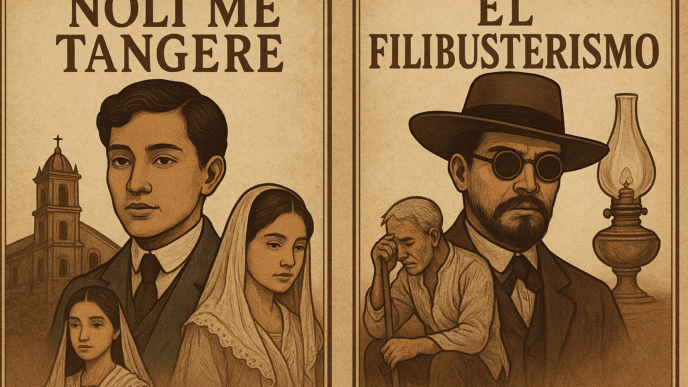

Rizal absorbed this truth not as an academic observation but as a wound in his own home. It became the emotional foundation of his later critiques of the legal system in Noli Me Tangere, where characters like Sisa, Basilio, and Crispin suffer under similar injustices.

Teodora’s ordeal became a prototype for the recurring theme in Rizal’s writings — that the suffering of mothers, families, and ordinary people is proof of a broken society that demands reform.

Freedom Earned Through Persistence

After years of legal struggle, the case against Teodora eventually collapsed. Even the corrupt officials who pursued her imprisonment could not sustain the false charges. Her release, however, was not simply a victory of law; it was a testament to her strength.

She emerged from prison weakened in body but unbroken in spirit. Instead of retreating into silence, she continued teaching her children, guiding them with a moral clarity sharpened by hardship. She reminded them — and José, in particular — that education, virtue, and courage were the true weapons against injustice.

Her endurance became a moral anchor for Rizal and a blueprint for the ethical fiber he demanded from a new Filipino nation.

Lasting Impact on Rizal’s Vision for the Philippines

The imprisonment of Doña Teodora shaped Rizal’s political soul. It taught him that reform was not an abstract principle but a response to real human suffering. It pushed him toward the pursuit of knowledge, believing that an enlightened Filipino could never again be easily oppressed. It deepened his empathy for victims of injustice and sharpened his critique of colonial and clerical abuses.

Most importantly, it taught him that love of country begins with love of family — that the nation is but a larger version of the home, and that no country can prosper when its people are humiliated in their own land.

Years later, as Rizal wrote his novels, essays, and letters, the memory of his mother’s chains remained with him. It was not revenge that drove him, but the desire to build a society where no mother, no family, no Filipino would be treated as she had been.