Quick Summary

Rizal was shaped by a remarkable family whose discipline, education, moral courage, and political awareness created the foundation for his genius. Their sacrifices, values, and suffering helped form the man who would become the nation’s foremost reformist and thinker.

Introduction

Long before Jose Rizal became a novelist, reformer, and martyr, he grew up in a busy, book-filled, multilingual household where learning, industry, and moral conviction defined daily life.

The Mercado-Rizal clan was not merely a backdrop to his biography; it was the domestic republic that raised him, financed his education, sharpened his conscience, preserved his writings, and at critical moments absorbed the blows directed at him.

Any understanding of Rizal must begin with the family that shaped his mind and character.

The Mercado Line: Work Ethic, Prudence, and Quiet Leadership

Rizal’s father, Francisco Mercado, came from the prosperous and respected Mercado clan of Biñan and Calamba. The Mercados had built their status through hard work, careful land management, and service within the principalia. Their prosperity was rooted in discipline rather than privilege. Even the family name reflects the complexities of colonial life; an ancestor adopted “Mercado” in the mid-1700s to avoid reprisals after agrarian tensions.

Francisco inherited the clan’s steady temperament. He managed multiple fields and orchards on the Dominican hacienda with quiet responsibility. He was not flamboyant; his influence flowed from patience, integrity, and restraint. From him, Rizal learned thrift, humility, and the belief that one’s worth is measured not by title but by conduct.

The Alonso Line: Education, Intellectual Tradition, and Fierce Moral Will

On his mother’s side, Rizal was heir to the Alonso and Quintos families, known for their literacy, sharp wit, and strong sense of justice. His mother, Teodora Alonso, was one of the most educated women of her generation. She studied reading, literature, business, mathematics, and spirituality. She personally taught Rizal to read, nurtured his imagination, and modeled intellectual discipline.

Teodora’s courage shaped Rizal’s moral compass. In 1872, she was imprisoned for more than two years over a false poisoning charge connected to a family dispute. Dragged on foot from Calamba to Santa Cruz, she endured humiliation but never surrendered her dignity. Her eventual release — later said to have been influenced by the pleas of her youngest daughter, Soledad — was a formative event for young Jose. Witnessing his mother’s endurance taught him the meaning of justice violated and courage upheld.

A Household of Means, Books, and Conscience

The Rizal home in Calamba was large, active, and unusually sophisticated for its time. It was the first in town to own a piano and a substantial personal library. Books from Spain, France, and Germany lay beside local devotional works and practical manuals. The family valued learning so deeply that all daughters received formal education — uncommon in a colonial society where women’s schooling was often minimal.

The household blended Tagalog, Chinese, and Spanish influences. Their cultural identity reflected the layered ancestry of both parents, including a Chinese forebear, Lam-co, who adopted the Christian name Domingo Mercado in the late 1600s. This mixture of identities later shaped Rizal’s nuanced sense of belonging — Filipino yet cosmopolitan, rooted yet outward-looking.

Their comfort did not shield them from colonial hostility. Their prosperity, literacy, and independence made them easy targets when Rizal’s writings angered the friars.

The Obligation of Names: Mercado, Rizal, and Realonda

In 1849, Governor-General Narciso Clavería implemented a decree mandating standardized surnames across the archipelago. The family adopted the additional surname “Rizal,” derived from ricial, meaning “new growth” or “green fields,” while Teodora revived the old maternal name “Realonda.”

Paciano later urged the young Jose to use “Rizal” as his public name — a protective measure to distance him from the politically monitored “Mercado.” This choice shaped history. The world would know him not as Jose Mercado but as Jose Rizal.

Paciano: The Political Elder and Quiet Architect

Paciano Mercado, Rizal’s only brother, exerted an influence as profound as that of their parents. Ten years older, Paciano had lived with and worked for Father Jose Burgos, one of the priests executed after the 1872 Cavite Mutiny. The trauma of Burgos’s death and the constant surveillance Paciano endured afterward made him acutely aware of colonial injustice.

He became Jose’s first political teacher and later his protector. Paciano escorted him to Biñan and Manila, supported him financially during his studies in Europe, managed family matters in his absence, and after 1896 joined the revolution as a general. His steadfast loyalty formed a political and emotional backbone that the hero depended on throughout his life.

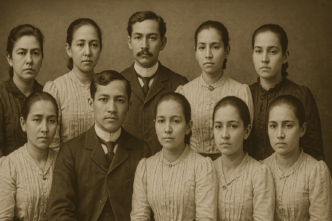

Sisters as the Family’s Hidden Strength

Rizal’s nine sisters played enormous roles in supporting his education, preserving his writings, spreading his ideas, and safeguarding his memory. Their contributions form one of the most moving aspects of the family story.

Saturnina (“Neneng”) helped manage finances and later facilitated the Tagalog translation of Noli Me Tangere — expanding its reach among Filipinos.

Narcisa tracked down Rizal’s unmarked grave after his execution, identifying it through the reversed initials “RPJ.” Her persistence ensured that his remains were preserved for future generations.

Lucia, whose husband Mariano Herbosa was denied a Christian burial due to suspected association with Rizal’s ideas, inspired the essay “Una profanación.” Her daughter, Delfina Herbosa de Natividad, later helped sew the first Philippine flag in Hong Kong.

Trinidad (“Trining”) secured Rizal’s final poem, Mi Último Adiós, hidden in an alcohol stove given to her the night before his execution. She later helped found one of the earliest women’s civic organizations in the country.

Josefa became a member of the Katipunan and, in some accounts, led its women’s chapter — evidence that the Rizal women were political actors, not passive observers.

Soledad (“Choleng”), the youngest, is remembered for her boldness as a child in advocating for her mother during the imprisonment ordeal.

Taken together, the sisters formed the logistical, emotional, and political network that enabled Rizal’s work. They financed his studies, kept his manuscripts safe, documented his final hours, and ensured the survival of the family’s legacy.

Uncles and the Formation of Early Habits of Mind

Rizal’s maternal uncles — Jose Alberto, Gregorio, and Manuel — each cultivated a different aspect of his early development. One encouraged his interest in the arts, another stimulated his love for books, and a third guided his physical training. These influences explain the remarkable versatility Rizal later displayed: sculptor, reader, linguist, athlete, and scholar.

The Calamba Crucible: When the Family Paid the Price

As Rizal’s reputation grew, so did surveillance and harassment from the friars. When he exposed the rent abuses on the Dominican estate in the late 1880s, the retaliation was swift and brutal. By 1890, the Mercado-Rizals were ordered to vacate the lands they had farmed for generations. Their home was seized, possessions thrown into the street, and many family members forcibly exiled from Calamba.

This collective punishment shaped Rizal’s conviction that reform could not come from silence. The suffering of his family became a national symbol of the injustices that ordinary Filipinos endured.

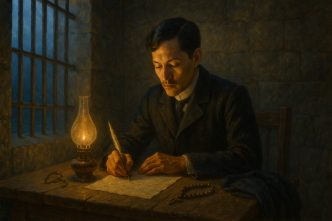

Last Rites of a Poem, First Rites of a Nation

The family’s role in the final hours of Rizal’s life demonstrates the depth of their loyalty. On December 29–30, 1896, they retrieved, copied, and preserved Mi Último Adiós, located his secret grave, carried his final messages, and safeguarded papers that would later become essential national documents.

What happened in Fort Santiago did not remain a family secret; it became part of the nation’s archive. The little stove that held the poem, the women who deciphered it, and the siblings who secured his remains transformed private grief into public memory.

What the Rizal Family Made Possible

When all threads are drawn together, a pattern emerges:

Rizal was never the isolated genius he was sometimes made out to be. He was the product of a household that valued learning, defied injustice, nurtured emotional resilience, and practiced civic responsibility. Their collective sacrifices — financial, emotional, and political — made his work possible.

The mother who taught him.

The father who steadied him.

The brother who guided him.

The sisters who supported, protected, and carried forward his legacy.

The uncles who shaped his talents.

The extended family who absorbed the consequences of his activism.

The hero recognized by the nation on December 30, 1896, was the result of a family culture decades in the making — a domestic republic that raised a man for a country still waiting to be born.

Conclusion

Rizal’s achievements cannot be separated from the family that shaped him. Their integrity, resilience, and devotion provided the foundation for his intellectual and moral development. His writings and martyrdom echo with the voices of the household that nurtured him — a family whose sacrifices and strengths became inseparable from the birth of a nation.

To read Rizal’s full life story, see Jose Rizal: A Complete Biography.