Quick Summary

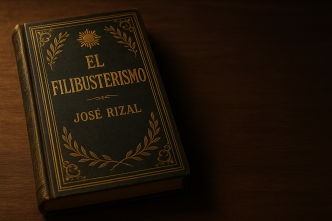

Mi Último Adiós is Jose Rizal’s final poem, composed on the eve of his execution in 1896. Hidden inside an alcohol burner and discovered after his death, the poem stands as a luminous farewell to his country, offering a vision of sacrifice, hope, and the awakening of the Filipino nation.

Background

Jose Rizal wrote Mi Último Adiós during his final night in Fort Santiago on December 29, 1896. Although he had spent months imprisoned, interrogated, and condemned, Rizal approached his last hours with composure. Instead of anger or despair, he turned to poetry. The result was a 14-stanza masterpiece written in delicate, controlled verse.

Rizal did not give the poem a title. He folded the manuscript, placed it inside an alcohol burner, and entrusted it to his sister Trinidad with the quiet instruction, “There is something inside.” Only after his execution at Bagumbayan the following morning was the poem discovered intact.

The poem circulated by hand in secret before eventually becoming public. Revolutionary leaders cherished it. Scholars studied it. Families recited it in private. It became Rizal’s intellectual and emotional testament: a farewell to his loved ones, an offering of his life to the Philippines, and an expression of unwavering faith that the nation would one day be free.

Full Poem: Mi Último Adiós (Original Spanish Text)

Adiós, Patria adorada, región del sol querida,

Perla del mar de oriente, nuestro perdido Edén!

A darte voy alegre la triste mustia vida,

Y fuera más brillante, más fresca, más florida,

También por ti la diera, la diera por tu bien.

En campos de batalla, luchando con delirio,

Otros te dan sus vidas sin dudas, sin pesar;

El sitio nada importa, ciprés, laurel o lirio,

Cadalso o campo abierto, combate o cruel martirio,

¡Lo mismo es si lo piden la patria y el hogar!

Yo muero cuando veo que el cielo se colora

Y al fin anuncia el día tras lóbrego capuz;

Si grana necesitas para teñir tu aurora,

Vierte la sangre mía, derrámala en buen hora

Y dórela un reflejo de su naciente luz.

Mis sueños cuando apenas muchacho adolescente,

Mis sueños cuando joven ya lleno de vigor,

Fueron el verte un día, joya del mar de oriente,

Secos los negros ojos, alta la tersa frente,

Sin ceño, sin arrugas, sin manchas de rubor.

Ensueño de mi vida, mi ardiente vivo anhelo,

¡Salud te grita el alma que pronto va a partir!

¡Salud! ¡Ah, que es hermoso caer por darte vuelo,

Morir por darte vida, morir bajo tu cielo,

Y en tu encantada tierra la eternidad dormir!

Si sobre mi sepulcro vieres brotar un día

Entre la espesa yerba sencilla, humilde flor,

Acércala a tus labios y besa al alma mía,

Y sienta yo en mi frente bajo la tumba fría,

De tu ternura el soplo, de tu hálito el calor.

Deja a la luna verme con luz tranquila y suave,

Deja que el alba envíe su resplandor fugaz,

Deja gemir al viento con su murmullo grave,

Y si desciende y posa sobre mi cruz un ave,

Deja que el ave entone su cántico de paz.

Deja que el sol, ardiendo, las lluvias evapore

Y al cielo tornen puras, con mi clamor en pos;

Deja que un ser amigo mi fin temprano llore

Y en las serenas tardes cuando por mí alguien ore,

¡Ora también, oh Patria, por mi descanso a Dios!

Ora por todos cuantos murieron sin ventura,

Por cuantos padecieron tormentos sin igual,

Por nuestras pobres madres que gimen su amargura;

Por huérfanos y viudas, por presos en tortura

¡Y ora por ti que veas tu redención final!

Y cuando en noche oscura se envuelva el cementerio

Y solos sólo muertos queden velando allí,

No turbes su reposo, no turbes el misterio,

Tal vez acordes oigas de cítara o salterio,

¡Soy yo, querida Patria, yo que te canto a ti!

Y cuando ya mi tumba de todos olvidada

No tenga cruz ni piedra que marquen su lugar,

Deja que la are el hombre, la esparza con la azada,

Y mis cenizas, antes que vuelvan a la nada,

El polvo de tu alfombra que vayan a formar.

Entonces nada importa me pongas en olvido.

Tu atmósfera, tu espacio, tus valles cruzaré.

Vibrante y limpia nota seré para tu oído,

Aroma, luz, colores, rumor, canto, gemido,

¡Constante repitiendo la esencia de mi fe!

Mi patria idolatrada, dolor de mis dolores,

Querida Filipinas, oye el postrer adiós.

Ahí te dejo todo, mis padres, mis amores.

Voy donde no hay esclavos, verdugos ni opresores,

Donde la fe no mata, donde el que reina es Dios.

¡Adiós, padres y hermanos, trozos del alma mía,

Amigos de la infancia en el perdido hogar!

¡Dad gracias que descanso del fatigoso día;

Adiós, dulce extranjera, mi amiga, mi alegría!

¡Adiós, queridos seres, morir es descansar!

Analysis

Reading Mi Último Adiós in its original Spanish reveals the musicality, rhythm, and emotional precision that translations cannot fully capture. Rizal wrote with a classical sense of structure, balancing beauty with restraint. The poem is deeply personal yet unmistakably nationalistic, weaving private sorrow with public duty.

The opening stanza sets the tone: a gentle farewell, an offering of life, and an unshaken sense of purpose. Rizal transforms the idea of sacrifice into something noble. For him, death gains meaning only when it serves the homeland. He envisions his blood illuminating the dawn, his memory living through wind, moonlight, and birdsong, and his voice whispering across the land even after he is gone.

Recurring images of dawn and night underscore his belief that suffering precedes awakening. Dawn symbolizes the freedom he will never witness. Night represents oppression, uncertainty, and the weight of colonial rule. Yet the poem radiates serenity. Rizal faces death without hatred. Instead, he embraces the natural world as his final companion.

The Spanish text also reveals his intimacy. Rizal speaks to childhood friends, to parents and siblings, and perhaps most poignantly, to an unnamed “dulces extraños,” scholars often interpret as Josephine Bracken. These lines humanize the hero and emphasize that martyrdom did not erase his affections.

A century after it was written, Mi Último Adiós remains one of the foundational literary works in Philippine history. It is the crystallization of Rizal’s ideals: love of country, intellectual courage, moral clarity, and the belief that freedom requires both struggle and sacrifice. The poem lives on because it speaks not only of death, but of hope — the hope that a nation may rise through the dignity and conscience of its people.

Continue your exploration of Rizal’s final message by reading “My Last Farewell,” the English translation, and “Huling Paalam,” the Tagalog rendering of Mi Último Adiós.