Quick Summary

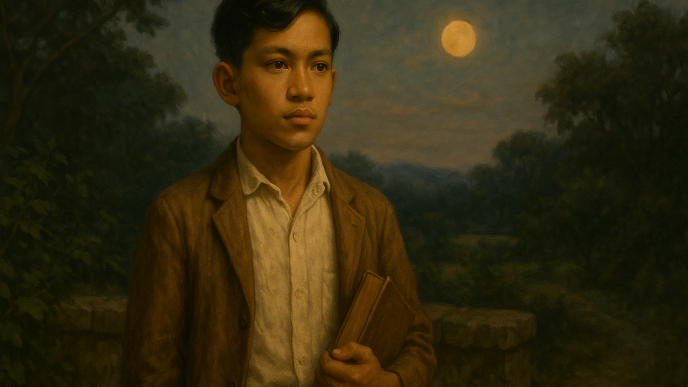

“To the Philippines” is one of Jose Rizal’s early patriotic poems, written during his youth as he began shaping his identity as both a writer and a Filipino nationalist. The poem reflects his longing for his homeland, his gratitude for the culture that shaped him, and his desire to dedicate his talents to the country he would later die for.

Background

“To the Philippines,” originally titled A la Patria, belongs to Rizal’s early period as a student and young intellectual. Unlike Mi Último Adiós, which he wrote before his execution, this poem comes from a time when he was still discovering the power of language, art, and education to express love of country. It captures the emotional roots of his nationalism long before it matured into the decisive and sacrificial patriotism that would define his final years.

Even as a young man, Rizal carried within him a deep sense of connection to the land of his birth. He had seen enough injustice and inequality to know that the Philippines was a nation in need of awakening. But at this stage of his life, his resistance took the form of imagination rather than confrontation. Through verse, he expressed gratitude to the homeland that nurtured his early dreams, molded his identity, and filled him with the cultural richness that would later fuel his revolutionary writings.

“To the Philippines” is therefore both youthful and profound. It reveals a poetic voice still in formation yet already firm in its devotion. It sets the foundation for the larger body of patriotic literature Rizal would eventually produce, culminating in works that became symbols of national awakening.

Full Poem: To The Philippines

Warm and beautiful like a houri of yore,

as gracious and as pure as the break of dawn

when darling clouds take on a sapphire tone,

sleeps a goddess on the Indian shore.

The small waves of the sonorous sea assail

her feet with ardent, amorous kisses, while

the intellectual West adores her smile;

and the old hoary Pole, her flower veil.

My Muse, most enthusiastic and elate,

sings to her among naiads and undines;

I offer her my fortune and my fate.

With myrtle, purple roses, and flowering greens

and lilies, crown her brow immaculate,

O artists, and exalt the Philippines!

Analysis

“To The Philippines” is a compact but revealing window into Rizal’s early poetic mind. The poem is a Petrarchan-style sonnet, rich with classical references: houris from Islamic tradition, Naiads and Undines from Greco-Roman and European mythology, and personifications of the West and the Pole. By weaving these images together, Rizal brings the Philippines into the same imaginative space as Europe’s mythic and cultural heritage. The message is subtle but powerful: his country belongs on the same artistic and moral stage as any Western nation.

The Philippines appears here as a sleeping goddess, not yet awakened, but already admired by the world. The “sonorous sea” kisses her feet, the West adores her smile, and even the distant Pole honors her “flowered veil.” This global gaze anticipates Rizal’s later belief that the Philippines deserved not pity, but respect. Even before openly attacking colonial abuses, he was already reframing how his homeland should be seen: not as a backwater, but as a place of beauty and potential.

Another important detail is the role of art. The poem was written for a sculptors’ album, and Rizal directly addresses “artists” in the final lines, urging them to crown the Philippines with myrtle, roses, and lilies and to “exalt the Philippines.” He envisions art as an instrument of honor: sculpture, painting, and poetry become ways to elevate the country’s image in the eyes of the world and in the hearts of Filipinos themselves.

Compared to his later, more overtly political works, “To The Philippines” feels almost serene. There is no explicit mention of oppression or injustice. Yet the poem is already quietly revolutionary. By dignifying the Philippines as a goddess worthy of solemn praise, Rizal lays emotional groundwork for the sharper critiques to come. It is a poem of admiration rather than protest, but that admiration is itself an act of resistance against a colonial system that belittled the colonized.

In your larger Rizal collection on JoseRizal.com, this sonnet sits naturally beside Mi Último Adiós, “To the Philippine Youth,” and “Huling Paalam.” It shows the beginning of a trajectory: a young poet learning to love his country in verse, before that love matured into the full, demanding patriotism that would eventually cost him his life.