QUICK SUMMARY

Jose Rizal’s major works — novels, essays, poems, letters, and scientific writings — formed the intellectual core of the Philippine nationalist movement. These writings exposed social injustice, reconstructed Filipino identity, and offered a roadmap for reform and liberation.

Introduction

Jose Rizal’s body of writing is one of the most influential literary and political collections in Southeast Asian history. Each text he produced, whether a novel, a poem, an essay, or a private letter, carried a purpose beyond artistic expression.

His works engaged directly with the conditions of colonial rule, challenged entrenched abuses, and gave Filipinos a vocabulary for understanding themselves as a nation. Through careful observation, disciplined study, and moral clarity, he transformed lived reality into literature that awakened consciousness.

Rizal’s writings were shaped by his experiences abroad, his scientific interests, and his profound compassion for ordinary Filipinos. He wrote not from the margins but from the heart of a society in crisis. His major works show a mind constantly analyzing, questioning, and striving to elevate his country. To study them is to witness a nation learning to see itself.

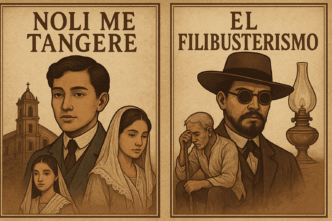

The Novels: Noli Me Tangere and El Filibusterismo

Rizal’s novels stand as the most powerful literary achievements in Philippine history. They combine social criticism with vivid storytelling, revealing the inner workings of colonial society and the moral consequences of injustice. Through these two books, Rizal opened a national conversation about identity, power, and the future of the Filipino people.

Noli Me Tangere

Noli Me Tangere, published in Berlin in 1887, offered an unflinching portrayal of Philippine society. It was the first Filipino novel to fully articulate the social, political, and psychological realities of Spanish rule. Rizal exposed corruption within religious orders, abuses of the civil guard, and the fragility of a system built on fear.

The novel’s characters — from the idealistic Crisóstomo Ibarra to the oppressed Sisa and her sons — represented real struggles faced by Filipino families. Through them, Rizal showed how injustice seeps into every part of life, from education to religion to family structures. The Noli confronted not only abuses of power but also the internalized habits of silence and submission that had shaped colonial society.

Its publication shook both colonial authorities and educated Filipinos. For the first time, the country saw itself honestly depicted through the eyes of one of its own.

El Filibusterismo

El Filibusterismo, published in Ghent in 1891, was a deeper, sharper critique of a society that had refused to change. Darker in tone and more urgent in theme, the novel explored the failure of reform through the transformation of Ibarra into Simoun, a man driven not by hope but by despair.

The novel highlighted student struggles, institutional hypocrisy, and the desperation that arises from unrelenting oppression. Its final chapters — filled with betrayal, death, and unrealized revolution — drove home Rizal’s message that violence grows naturally from systems that refuse justice. But even in its somber message, El Fili calls readers to moral reflection, urging them to confront injustice without sacrificing humanity.

The two novels together form a sweeping portrait of a society on the brink, offering both diagnosis and warning.

Essays and Political Writings

Rizal’s essays provided the intellectual backbone of the Propaganda Movement. They dissected colonial policies using logic, history, and scientific reasoning, countering racist narratives with evidence-based arguments.

The Philippines a Century Hence

In this four-part essay published in La Solidaridad, Rizal traced the historical forces shaping the Philippines and imagined possible futures. He predicted rising nationalism, economic awakening, and the eventual collapse of Spanish control. His analysis was grounded in global trends: the weakening of empires, the spread of liberal ideas, and the growing desire for local autonomy. He asked readers to see themselves as part of a larger historical movement toward freedom.

The Indolence of the Filipinos

Rizal challenged the colonial accusation of inherent Filipino laziness by revealing its roots in economic exploitation, forced labor, environmental factors, and lack of opportunity. He approached the issue not emotionally but analytically, showing how a society denied education and mobility naturally develops patterns of survival rather than ambition. The essay dismantled racist logic and restored dignity to the Filipino character.

On the Education of the Masses

Rizal believed that education was the foundation of a strong nation. He called for schools that taught science, critical thinking, and civic responsibility. For him, education was not a luxury; it was a right that would uplift communities and break the cycle of dependency.

Other Political Essays

He also wrote about freedom of speech, the importance of civic participation, and the abuses of friar power. His essays circulated among Filipino expatriates, shaping the reform movement that eventually evolved into revolution.

Poetry and National Identity

Rizal’s poetry reveals the emotional core of his nationalism. His verses communicate longing, love for the motherland, devotion to truth, and the sacrifices required of a free people.

Mi Último Adiós

Written secretly on the night before his execution, Mi Último Adiós stands as a testament to his calm acceptance of death in exchange for his country’s future. The poem blends faith, patriotism, and hope, suggesting that martyrdom nourishes national awakening. Every stanza carries a sense of peace rather than anger, reflecting his belief that love — not hatred — drives true freedom.

A La Juventud Filipina

This early poem celebrated Filipino youth as the hope of the nation. It called on the younger generation to pursue excellence and uplift the country with talent and intellect. The poem became foundational in shaping the idea of a “nation of potential.”

To the Flowers of Heidelberg

Written during his studies in Germany, this poem expressed homesickness and the symbolic connection between distant landscapes and his beloved homeland. It showed that exile sharpened his love for the Philippines.

Other Poems

Rizal’s lesser-known poems — including works on friendship, love, nature, and patriotism — round out his identity as a writer whose emotions were inseparable from his commitment to his country.

Letters, Diaries, and Personal Writings

Rizal’s personal writings provide insight into the evolution of his thought. They reveal his strategic mind, his moral convictions, and his deep affection for family and friends.

Letters

His letters to Ferdinand Blumentritt show his intellectual curiosity and cultural openness. His correspondence with reformists like Marcelo H. del Pilar and Graciano López Jaena reveal his tactical approach to political change. Letters to his family reflect his tenderness, vulnerability, and sense of responsibility.

Diaries

Rizal’s diaries from Dapitan reveal a deeply human side: a doctor treating the poor, a teacher educating children, a scientist cataloging flora and fauna, and a community builder guiding projects. These writings show that even in exile, he lived with purpose.

Scientific, Cultural, and Linguistic Contributions

Rizal’s curiosity extended beyond literature and politics. He explored Philippine identity through research and documentation.

Annotations of Morga’s Sucesos de las Islas Filipinas

By annotating Morga’s 1609 chronicle, Rizal revised the colonial narrative of Filipino inferiority. He highlighted achievements in agriculture, metallurgy, trade, and governance before the arrival of Spain. This work restored Filipino self-respect and countered centuries of cultural erasure.

Studies on Languages and Cultures

Rizal documented Tagalog grammar, recorded folktales, studied indigenous customs, and researched local plants and animals. His scholarship helped preserve Philippine heritage and encouraged pride in local knowledge.

Why Rizal’s Works Endure

Rizal’s works endure because they articulate universal values: justice, dignity, compassion, and the search for truth. They illuminate the moral responsibilities of citizens and the dangers of unchallenged authority. They also remind Filipinos of their long history of resilience, reminding each generation that national identity is built through both thought and action.

Conclusion

The major works of José Rizal form a rich, multifaceted legacy. His novels awakened a nation. His essays sharpened the intellectual tools of reform. His poems captured the soul of the Filipino. His letters and diaries revealed a life of service, and his scientific work helped reconstruct a proud pre-colonial identity. Together, his writings continue to guide the Philippines in its ongoing journey toward understanding its past and shaping its future.