Quick Summary

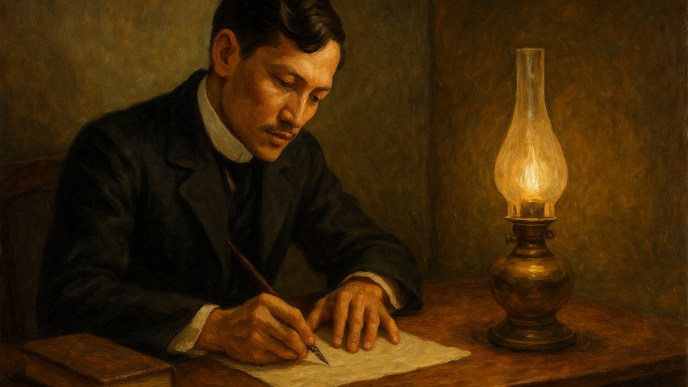

“My Last Farewell” (the English translation of Mi Último Adiós), is Jose Rizal’s final poem, written on the eve of his execution in 1896. Hidden in an alcohol stove and passed to his family after his death, it remains one of the most powerful articulations of love for the Philippines and the sacrifices demanded by freedom.

Background

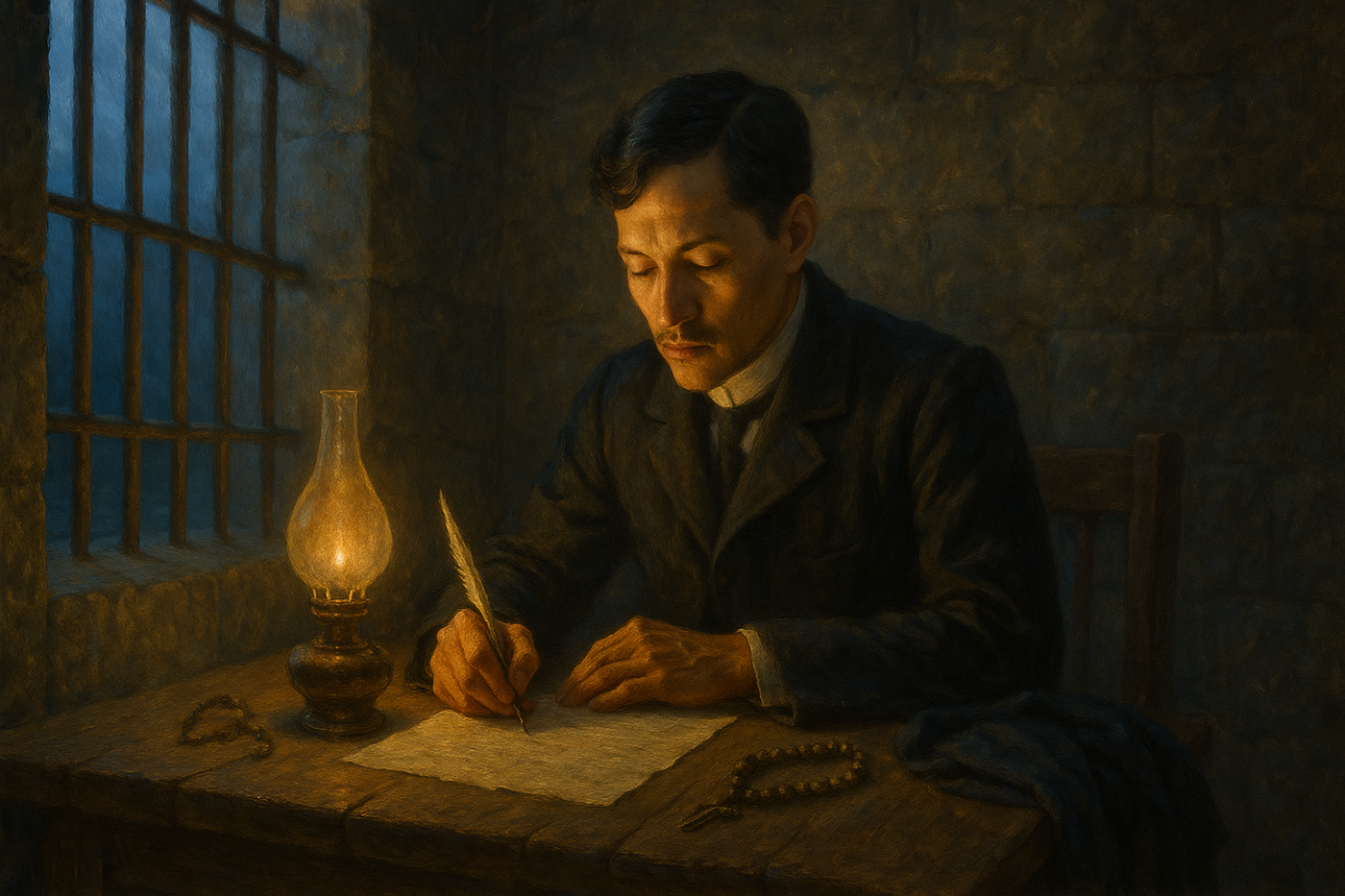

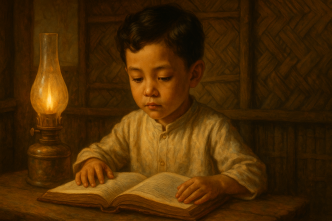

“My Last Farewell,” originally untitled in Rizal’s handwriting, was composed on December 29, 1896, during his final night in Fort Santiago. With his execution scheduled for the following morning, Rizal turned to poetry not as an act of despair but of clarity, courage, and profound patriotism. Manila trembled under colonial tension, and the revolution he had long warned Spain about was beginning to break open.

Rizal wrote his final poem on a single piece of paper, folded it carefully, and hid it inside an alcohol burner. When his sister Trinidad visited, he whispered, “There is something inside.” Hours later, after Rizal’s execution at Bagumbayan, the poem was recovered — a quiet document of farewell that soon resonated across the archipelago.

The poem’s tone is strikingly serene. Rizal refuses to meet death with bitterness. Instead, he treats his sacrifice as a final offering to his beloved country. He imagines his blood enriching the soil, his memory living on in nature, and the Philippines awakening to the dawn of freedom. The poem became a treasured artifact among reformists and revolutionaries alike, circulating in handwritten copies long before it was printed.

Full Poem: My Last Farewell (English Translation)

Farewell, dear Fatherland, clime of the sun caress’d,

Pearl of the Orient seas, our Eden lost!

Gladly now I go to give thee this faded life’s best,

And were it brighter, fresher, or more blest,

Still would I give it thee, nor count the cost.

On the field of battle, ‘mid the frenzy of fight,

Others have given their lives, without doubt or heed;

The place matters not—cypress or laurel or lily white,

Scaffold or open plain, combat or martyrdom’s plight,

‘Tis ever the same, to serve our home and country’s need.

I die just when I see the dawn break,

Through the gloom of night, to herald the day;

And if color is lacking my blood thou shalt take,

Pour’d out at need for thy dear sake,

To dye with its crimson the waking ray.

My dreams, when life first opened to me,

My dreams, when the hopes of youth beat high,

Were to see thy lov’d face, O gem of the Orient sea,

From gloom and grief, from care and sorrow free;

No blush on thy brow, no tear in thine eye.

Dream of my life, my living and burning desire,

All hail! cries the soul that is now to take flight;

All hail! And sweet it is for thee to expire;

To die for thy sake, that thou mayst aspire;

And sleep in thy bosom eternity’s long night.

If over my grave some day thou seest grow

In the grassy sod, a humble flower,

Draw it to thy lips and kiss my soul so,

While I may feel on my brow in the still hour,

A kiss that is fresh with the fragrance I love.

Let the moon beam over me soft and serene,

Let the dawn shed over me its radiant flashes,

Let the wind with sad lament over me keen;

And if on my cross a bird should be seen,

Let it trill there its hymn of peace to my ashes.

Let the sun draw the vapors up to the sky,

And heavenward in purity bear my tardy protest;

Let some kind soul o’er my untimely fate sigh,

And in the still evening a prayer be lifted on high

From thee, O my country, that in God I may rest.

Pray for all those that hapless have died,

For all who have suffered the unmeasur’d pain;

For our mothers that bitterly their woes have cried,

For widows and orphans, for captives by torture tried;

And then for thyself that redemption thou mayst gain.

And when the dark night wraps the graveyard around

With only the dead in their vigil to see,

Break not my repose or the mystery profound,

And perchance thou mayst hear a sad hymn resound;

‘Tis I, O my country, raising a song unto thee.

And even my ashes may some day be thrown

To the winds, and over the fields be spread;

And still will I whisper, when fate is unknown,

And still will I cry, though men overthrow,

My undying faith in thee, my country, to thee!

My Fatherland ador’d, that sadness to my sorrow lends,

Beloved Filipinas, hear now my last farewell!

I give thee all: parents and kindred and friends;

For I go where no slave before the oppressor bends,

Where faith can never kill, and God reigns o’er all.

Farewell to you all, from my soul torn away,

Friends of my childhood in the home dispossessed!

Give thanks that I rest from the wearisome day!

Farewell to thee, too, sweet friend that lightened my way!

Beloved creatures all, farewell! In death there is rest!

Translation by Charles Derbyshire. Public domain.

Analysis

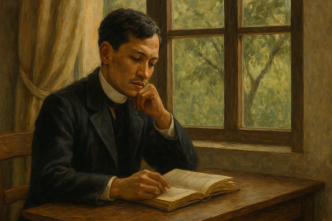

Using Charles Derbyshire’s translation brings out the solemn musicality of Rizal’s original Spanish, preserving the poem’s blend of tenderness, resignation, and unwavering patriotism. The language is elevated but never distant, reflecting Rizal’s classical education as well as his emotional clarity during his final hours.

A central theme in the poem is the transformation of personal sacrifice into national hope. Rizal envisions his blood coloring the dawn, symbolizing that freedom may arrive through the collective suffering of a people awakening to their identity. He imagines the natural world — moonlight, breezes, birdsong — carrying on his message long after his death, suggesting that the memory of sacrifice becomes part of the nation’s landscape.

The Derbyshire translation also preserves the poem’s emotional layering. Rizal’s farewell to life is gentle rather than anguished. He shifts from patriotism to intimate affection, addressing parents, friends, and a “sweet friend that lightened my way,” believed by many scholars to be Josephine Bracken. These final stanzas humanize him, reminding readers that behind the national hero was a man with a circle of loved ones whose grief would be personal and immediate.

Yet the poem always returns to the Philippines. Even in imagining his ashes scattered, Rizal expresses ongoing faith in the country’s eventual redemption. The poem closes not with fear but with peace — a rest earned through fidelity to one’s ideals.

“My Last Farewell” remains essential to understanding Rizal not only as a martyr, but as a writer whose final act was to offer beauty, clarity, and courage to a nation still in the process of imagining itself free.

Discover the full Spanish text in “Mi Último Adiós” and explore the Filipino version in “Huling Paalam,” the Tagalog translation that helped carry Rizal’s final message to the masses.

Happy birthday, our national hero, Dr. Jose P. Rizal. June 19, 2015. Overshadow our Philippine country with your heroic spirit.

Touching Poem, I like it! 🙂

It sad to see how, years after Rizal’s death the country still struggles to elect government officials who would serve the people instead of their personal interests. The blood of the martyrs who sacrificed everything for the cause of freedom in all but washed away in the flood of corruption. Hope this election brings about change for the better.