Quick Summary

Jose Rizal was exiled to Dapitan in 1892 because Spanish authorities viewed him as a growing threat. His writings exposed abuses, his reformist ideas stirred national consciousness, and the founding of La Liga Filipina alarmed officials who feared he could unite Filipinos toward organized resistance.

Introduction

The exile of Jose Rizal to Dapitan was not a random administrative decision. It was the result of years of rising tension between the colonial government, the friar establishment, and a widening circle of Filipinos awakened by his writings. Although Rizal would later transform Dapitan into a center of learning and community life, this period began with suspicion, political fear, and the culmination of grievances that the authorities had long held against him.

The Political Climate Before Exile

By the early 1890s, Rizal had become the most prominent voice calling attention to abuses in the Philippines. His novels, essays, and speeches had circulated widely, and although he consistently advocated peaceful reform, his influence troubled those in power. The publication of Noli Me Tangere and El Filibusterismo had already drawn the anger of the friars, who recognized themselves in the corrupt characters of the novels.

Even before his return to Manila in 1892, the colonial government monitored his activities in Europe. His involvement in the Propaganda Movement, his association with outspoken reformists, and his growing international reputation made him a symbol of Filipino intellectual awakening.

A Dangerous Return to the Philippines

Rizal’s decision to return to Manila on June 26, 1892 was an act of courage. Friends abroad urged him to stay away because they believed his life was in danger. Yet Rizal felt a moral obligation to stand with his countrymen. He hoped that honest dialogue with authorities would show that he sought peaceful change.

The colonial government, however, saw things differently. To them, his return meant renewed agitation. The friars in particular feared that his presence would strengthen reformist groups and further undermine their authority.

The Founding of La Liga Filipina

Only days after arriving, Rizal convened a meeting that resulted in the creation of La Liga Filipina. The organization aimed to promote unity, education, and civic responsibility among Filipinos. Its methods were peaceful, but its vision of a cohesive, organized Filipino community worried the authorities.

To a colonial state already anxious about dissent, the formation of such a group suggested the possibility of coordinated political action. Even without advocating violence, the Liga represented a new kind of threat: Filipinos thinking, planning, and acting together.

The Intercepted Letter and Old Suspicions

Rizal’s name soon became entangled in a political controversy involving a letter written by José Ma. Basa from Hong Kong. The letter, which spoke of reforms and the need for political awareness, was intercepted by Spanish authorities. Although Rizal did not write it, the appearance of his name in its content was enough to implicate him in sedition.

The authorities combined this new suspicion with older grievances. They had not forgotten his involvement in defending tenants during the Calamba agrarian dispute or the impact of his novels on public opinion. In their view, the return of a man who had caused so much embarrassment and unrest was reason enough for action.

Arrest and Deportation

On July 6, 1892, Rizal was arrested quietly in Manila. The investigation that followed did not uncover concrete evidence of rebellion. There were no weapons, no plans for revolt, and no record of him taking part in violent activity. But the government concluded that the mere presence of a man who had written such influential works posed a danger to public order.

Governor-General Eulogio Despujol approved the deportation. Exile was chosen because it neutralized Rizal without making him a martyr. It allowed the state to restrict his movements and influence while avoiding the explosive impact of a harsher punishment.

Why Dapitan Was Chosen

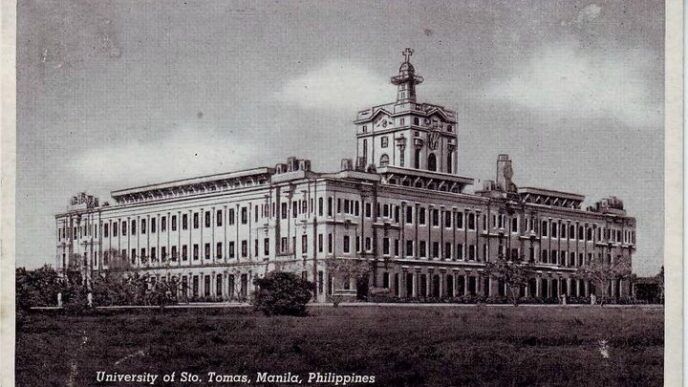

Dapitan, a remote town on the northern coast of Mindanao, was selected because of its isolation. Sending Rizal there kept him far from Manila, far from his reformist colleagues, and far from the networks that admired and supported him. The colonial government believed that distance would diminish his influence.

Dapitan also had a Spanish military presence, which ensured close surveillance. Authorities assumed that limited access to communication and travel would prevent him from inspiring or organizing Filipinos.

The Influence of the Friars

While the government issued the formal order, the religious orders were the most persistent force behind the push to remove Rizal from the capital. The friars had long considered him their most dangerous critic. His writings challenged their power, questioned their conduct, and exposed the injustices they committed.

The friars’ involvement in the Calamba eviction cases and their deep resentment over both Noli Me Tangere and El Filibusterismo shaped their attitude. They saw Rizal as an existential threat to their authority, and their pressure strongly influenced decisions made at the highest levels of colonial administration.

Exile as a Political Strategy

Exiling Rizal was a calculated move. Authorities believed that removing him from the public eye would weaken the reformist movement. They assumed that distance would erode his reputation. They hoped that time and obscurity would silence his influence.

What they did not foresee was how Rizal would use exile as a period of service, scholarship, and community building. Instead of fading into irrelevance, he became even more respected. His work in Dapitan revealed his commitment to education, public health, and civic improvement. The years intended to silence him ended up enhancing his legacy.

What His Exile Reveals

Rizal’s exile reflects the profound insecurity of the colonial regime. A single writer, armed only with intellect and ideals, frightened a powerful empire. His ideas challenged the assumptions that justified colonial rule, and his moral authority stirred a new sense of national identity among Filipinos.

The government feared what he represented: an educated Filipino capable of inspiring others to think critically about justice, dignity, and the future of their country.

Conclusion

Jose Rizal was exiled to Dapitan not because he committed a crime but because he symbolized a growing movement toward reform and national consciousness. His writings exposed abuses. His actions encouraged unity. His return home awakened hope.

The Spanish government believed that removing him from Manila would suppress that hope. Instead, the exile confirmed his stature as a leader whose influence extended far beyond his physical freedom. Dapitan became the stage on which his dedication to his people shone most clearly, revealing a patriot who continued to serve even under watchful eyes and forced isolation.

To read Rizal’s full life story, see Jose Rizal: A Complete Biography.