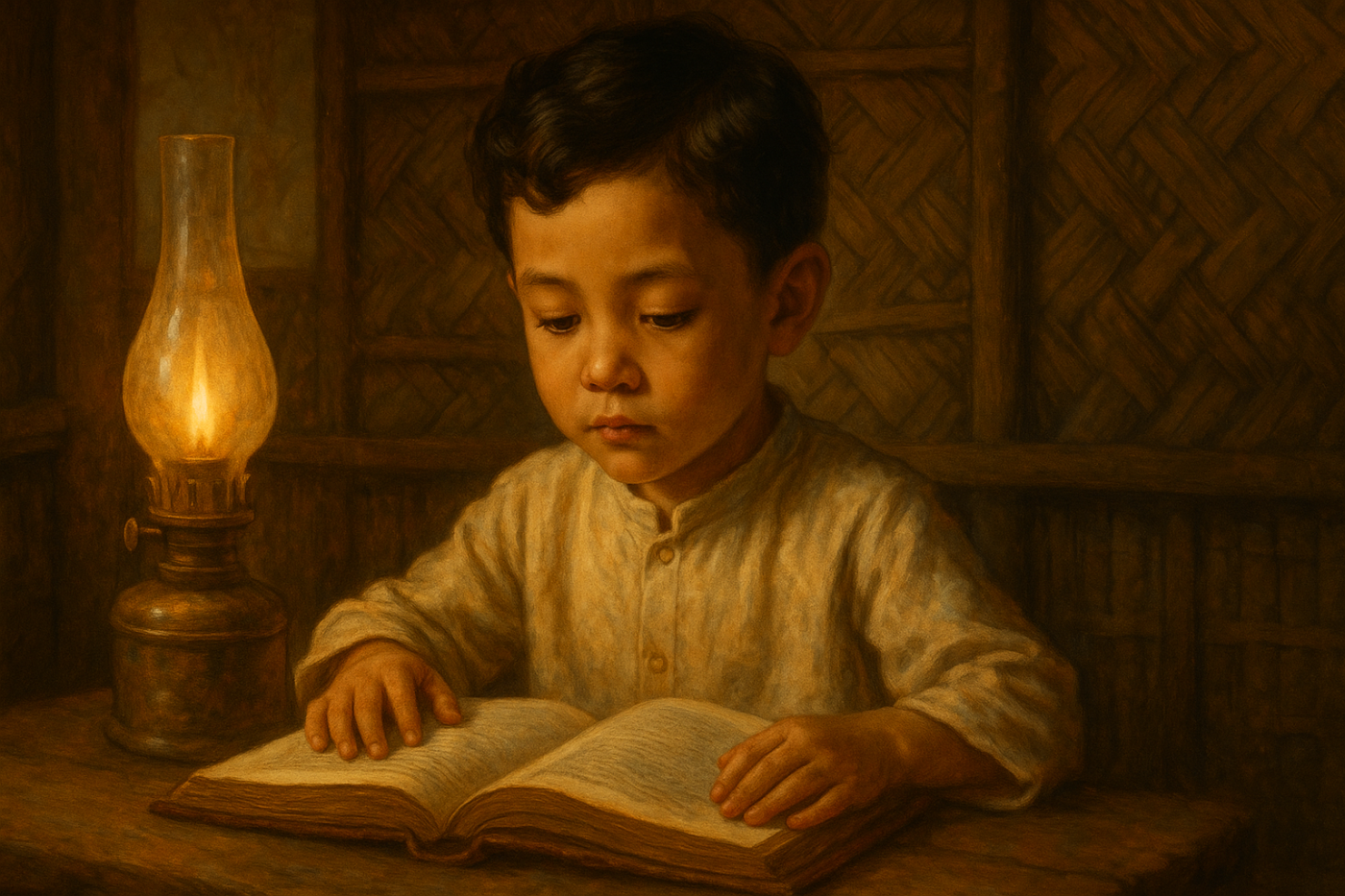

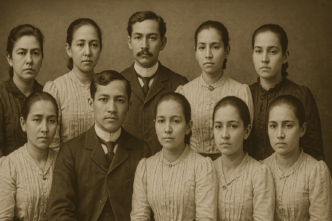

Jose Protacio Rizal was born on 19 June 1861 in Calamba, Laguna, the seventh of eleven children of Francisco Mercado and Teodora Alonso. His family’s relative comfort, their habits of study and prayer, and the beauty of lakeshore Calamba formed the cradle of a prodigy who would later on write novels that stirred both the consciousness and conscience of a nation.

A House of Prayer, Books, and Stories

In reminiscences published after his death, Rizal recalls evenings on the azotea with family prayers, then moonlit storytelling by his nurse — strands of wonder and discipline woven into nightly ritual. The same pages preserve his “first sorrow”: at age four, he lost his little sister Concha and wept “for love and grief,” a child’s grief that deepened his empathy early.

Teodora Alonso, his first teacher, taught him letters, catechism, and a watchful curiosity. Later NHCP essays would call her the central moral and intellectual influence of his youth, which squares with his own recollections of a mother who corrected firmly yet lovingly.

First Teachers and Early Training

Before formal school, private tutors came and went through the Calamba home. Rizal remembered an elderly tutor, his father’s former classmate, who taught him the rudiments of Latin while lodging with the family.

Family tradition also credits three maternal uncles for shaping him in complementary ways: Jose Alberto (arts), Gregorio (books and study), and Manuel (outdoor exercise and physical training). The picture that emerges is not of a lone genius so much as a boy intensively cultivated by kin.

Biñan: First Formal Schooling (1869–1871)

Rizal left Calamba for nearby Biñan and, under Maestro Justiniano Aquino Cruz, received his first structured lessons. A national historical marker in Biñan memorializes this period and the teacher who later urged the boy to seek higher studies in Manila.

In his own sketches, Rizal remembered Justiniano’s severity, schoolyard tussles, and a neighbor — Juancho, an elderly painter — who let him dabble at the easel. The mix of strict drills and small artistic freedoms suited him. He left Biñan on 17 December 1870/1871 (sources vary), a farewell he recounts with unusual detail.

A Child’s World Beyond Calamba

Rizal’s first big trip — 1868 — was a pilgrimage with his father to Antipolo, via the Pasig towns. He wrote later of the river journey’s delights, a hint of the observational habit that would flower in the travel diaries of his youth. The home itself, reconstructed today as Museo ni Jose Rizal Calamba, has been curated explicitly to evoke that childhood world: kitchen lessons, library discoveries, prayers in the bedroom, stories under the night sky.

Shockwaves at Age Eleven (1872)

Two blows fell in 1872. In February, the colonial state garroted the priests Gómez, Burgos, and Zamora (Gomburza) after the Cavite Mutiny — an injustice that would sear itself into Rizal’s memory (he later dedicated El Filibusterismo to them).

Around the same time his mother was arrested on a trumped-up charge in a family dispute and hauled to the province jail; Rizal’s memoir chapter “The Injustice Done My Mother” reads like a child’s awakening to law as lived power. Those months turned household piety into a political conscience.

Crossing Into Adolescence: Ateneo Municipal

In June 1872, Paciano took eleven-year-old Jose to Manila for entrance tests. After some hesitation (he was small and sickly-looking), Ateneo Municipal admitted him—thanks in part to the intercession of Magín Fernando and Manuel Xerez Burgos, nephew of the martyred Fr. Burgos.

From there his student record is well known; but the pivot from child to scholar only makes sense against the sturdy scaffolding of home and the shocks of that year.

How Childhood Shaped the Writer

- Language of feeling: The tenderness of family life and the wound of Concha’s passing recur in a humane, observant narrator—one who looks closely at the everyday sorrows of Sisa and the children of Noli Me Tángere.

- Habits of inquiry: Teodora’s lessons and his uncles’ tutelage encouraged study, drawing, and physical discipline—the same breadth evident in the adolescent who would later fence, sculpt, and annotate books with zeal.

- Sense of justice: The pairing of Gomburza’s execution and his mother’s ordeal gave him a child’s-eye view of arbitrary rule. His later reformism — legalist, literate, unflinching — looks like a straight line from 1872.

A Note on Memory and Sources

For Rizal’s childhood, the most revealing materials are Rizal’s own memoirs (preserved in English translation) and the NHCP’s site-specific histories and essays.

They show a boy formed in the ordinary cadences of a provincial household — prayer and chores, stories and school— yet pricked, early and sharply, by injustice. The child who listened on the azotea became the writer who taught a people to listen to itself.

To read Rizal’s full life story, see Jose Rizal: A Complete Biography.