Quick Summary

José Rizal became the Philippines’ national hero through a combination of Filipino admiration, revolutionary respect, and American colonial endorsement. His writings, peaceful reformist ideals, and powerful martyrdom aligned with the narratives the Americans wanted to promote, solidifying his place as the country’s central national figure.

Introduction

The story of how José Rizal became the national hero of the Philippines is more complex than many people realize. He did not receive the title through a single proclamation or law. Instead, his heroism emerged through a long process shaped by Filipino reverence, revolutionary interpretation, and ultimately, American colonial policy.

Understanding how Rizal became the national hero requires examining not only his contributions but the political forces and historical circumstances that elevated his memory during the early 20th century.

Filipino Revolutionaries First Elevated His Memory

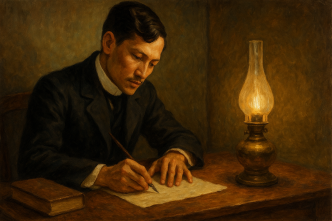

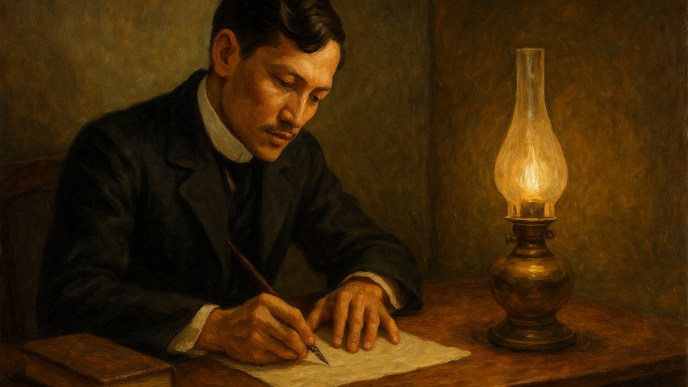

Even before the Americans arrived, Rizal had already been deeply admired by Filipinos involved in the Propaganda Movement and the Katipunan. His novels and essays exposed the failures of the colonial system, and many reformists saw him as the intellectual force behind the struggle for dignity. When he was executed on December 30, 1896, the emotional shock unified Filipinos in grief and outrage.

Members of the Katipunan, including Andrés Bonifacio and Emilio Jacinto, recited passages from Rizal’s writings and viewed his martyrdom as a symbol of the injustices that made revolution inevitable. Bonifacio himself reportedly read Mi Último Adiós aloud to revolutionaries. For many Filipinos of the late 19th century, Rizal embodied both the brilliance and the suffering of the nation. His sacrifice, though not tied directly to armed revolt, became a powerful moral justification for the revolution that followed.

The Americans Promoted Rizal as a Symbol of Peaceful Reform

When the United States took control of the Philippines in 1898, they sought ways to stabilize the country and minimize armed resistance. The Americans needed national symbols that encouraged unity but discouraged violent revolution. Rizal — a reformist who advocated peaceful change, education, and civic virtue — fit this narrative perfectly.

American colonial administrators such as Governor-General William Howard Taft viewed Rizal as an ideal figure to promote. His nonviolent stance aligned with American political messaging, making him safer to celebrate than more revolutionary leaders like Bonifacio or Aguinaldo. By highlighting Rizal’s intellectual approach rather than the militant forms of resistance, the Americans hoped to shape Filipino nationalism in a less confrontational direction.

This does not diminish Rizal’s genuine contributions, but it shows how his legacy was strategically emphasized during a crucial period.

Early American Policies Strengthened Rizal’s National Hero Status

During the early years of American rule, several important decisions solidified Rizal’s symbolic status.

In 1901, the Taft Commission established a Rizal Monument Committee and organized efforts to commemorate the site of his execution. The Americans also encouraged public observance of Rizal Day. By 1902, December 30 was officially declared a public holiday honoring his martyrdom.

Schools established under American supervision included Rizal’s life and works in their curriculum. Teachers emphasized his values of education, civic responsibility, and moral character — themes that aligned with American priorities for building a disciplined colonial society.

Through ceremonies, textbooks, and public monuments, the Americans helped integrate Rizal into the everyday consciousness of Filipino communities across the country. Over time, these efforts created a nationwide familiarity with his story and ideals.

Rizal’s Approach Matched What the Americans Wanted to Promote

Not all heroes were equally convenient for the Americans. Leaders who advocated armed struggle, such as Bonifacio or later Macario Sakay, threatened the American narrative of “benevolent assimilation.” Rizal, however, represented a form of nationalism rooted in education, reasoned reform, and peaceful civic action. He was easier to place within a story that emphasized progress under American guidance.

His execution by Spain — not by the Americans — also made him a safer figure to honor. Celebrating Rizal created no conflict with American authority, whereas elevating a revolutionary martyr executed by colonial forces might embolden resistance.

This political suitability helped shape the way he was remembered during the American period. His writings remained powerful, but the way they were framed in classrooms and ceremonies influenced how generations of Filipinos learned to imagine their national hero.

Filipino Scholars and Leaders Also Shaped His Heroic Image

While the Americans promoted Rizal, Filipino intellectuals, educators, and political leaders also played a central role in preserving his memory. Figures like Trinidad H. Pardo de Tavera, Claro M. Recto, and Teodoro Kalaw wrote extensively about Rizal’s contributions. They emphasized his compassion, intelligence, and moral courage, helping shape the narrative that he represented the best qualities of the Filipino people.

Filipino educators, especially during the 1920s and 1930s, further elevated his status by expanding the teaching of his works in public schools. Over time, the combination of public education, nationalist literature, and commemoration ceremonies made Rizal’s story inseparable from the story of the Filipino nation.

The Absence of a Formal Declaration Strengthened His Symbolic Power

A remarkable aspect of Rizal’s heroism is that no law, decree, or official proclamation ever declared him as the national hero of the Philippines. The Philippine government has never issued a formal designation naming him as such. Instead, Rizal’s heroism emerged naturally through national consensus.

His life and writings resonated deeply with Filipinos, who saw in him a symbol of dignity, courage, and justice. Over time, public opinion, education, literature, and cultural memory elevated him to the role. This grassroots recognition gives his heroism a unique authenticity. He did not become a hero because the state declared it — the state affirmed him because the people already believed it.

His Martyrdom United Filipinos Across Time

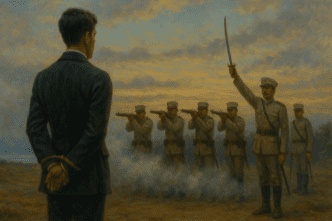

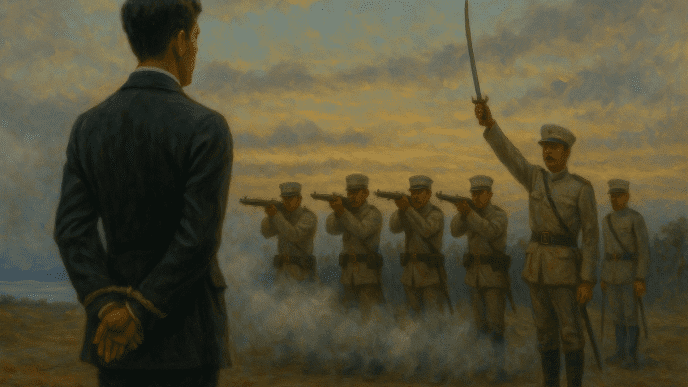

Rizal’s execution tied together the many strands of Filipino identity: justice, suffering, intellectual resistance, and profound love for the homeland. His death symbolized the failure of peaceful reform and the beginning of a more determined struggle for independence.

His final poem, Mi Último Adiós, became a prayer for the nation. His choice to face the riflemen with dignity became an example of moral courage. These moments ensured that Filipinos would continue to honor his memory long after the conflicts of colonial rule ended.

Conclusion

Rizal became the national hero of the Philippines not through a decree but through a confluence of powerful forces: the admiration of Filipino revolutionaries, the moral authority of his writings, the impact of his martyrdom, and the strategic support of American colonial policy. His life spoke to the highest aspirations of the Filipino people, while his death symbolized the greatest injustices they endured.

Today, Rizal stands as a hero not because one government proclaimed him so, but because generations of Filipinos — across regions, cultures, and eras — have continued to choose him. His story reflects the heart of the nation: a longing for freedom, dignity, education, and justice. That is how he became, and remains, the national hero of the Philippines.

Travel of JPR PLEASE

who is the author of this? and also the year and month of publications in order to make references and gave credit to the owner

Dr. Jose P. Rizal is more qualified than Andres Bonifacio because Rizal’s more educated than Andres Bonifacio. Andres Bonifacio was killed by betrayal of another Filipino, Emilio Aguinaldo, while Rizal was killed by the Spaniards. Only the death of Dr. Jose P. Rizal’s seem to be significant cause he was tried and executed by the Spaniards. Both his education and his patriotism and his end is a good example for newer generations to value educated leaders!