Quick Summary

Rizal never led troops nor planned an uprising, yet his novels, essays, political thought, and martyrdom supplied the Revolution with its moral center. His ideas shaped its goals, inspired its leaders, and awakened a national consciousness strong enough to ignite the first anti-colonial revolution in Asia.

Introduction

The Philippine Revolution of 1896 is often associated with the bravery of Andres Bonifacio, the strategies of Emilio Aguinaldo, and the sacrifices of countless Filipino fighters. Yet behind the battles lay an intellectual force that shaped the Revolution’s meaning and purpose: Rizal. Though he did not take up arms, his writings exposed the foundations of colonial oppression, his teachings gave direction to early reformists, and his martyrdom provided the emotional spark that transformed longing for change into a national uprising.

Rizal’s influence on the Revolution cannot be reduced to a few sentences. It emerges from decades of intellectual formation, political involvement, and moral leadership. His ideas informed how Filipinos understood their identity, their oppressors, and their aspirations. Without him, the Revolution would still have occurred, but it would not have carried the same moral gravity or cohesive vision of nationhood.

The Intellectual Climate Before the Revolution

Before the rise of nationalism, the Philippines existed as a collection of regions held together less by a shared identity than by shared colonization. Spaniards deliberately prevented national unity by reinforcing provincial divisions, limiting education, and controlling public discourse. Most Filipinos identified first with their town, then with their province. The archipelago lacked a common political vocabulary.

Rizal changed this landscape. His work paved the way for the concept of a Filipino nation — a community shaped not by colonial imposition but by cultural heritage, shared suffering, and collective hope. The Revolution could not have erupted without Filipinos first imagining themselves as one people. Rizal made that imagination possible.

How His Novels Sparked National Awakening

Noli Me Tangere and El Filibusterismo were more than works of fiction; they were mirrors reflecting a truth the colonial regime tried to hide. They exposed friar abuses, racial discrimination, corruption within the bureaucracy, and the psychological wounds inflicted on Filipinos.

These novels:

- Revealed the machinery of oppression

- Humanized the victims of injustice

- Showed how small abuses added up to a national crisis

- Encouraged Filipinos to question passivity

Characters like Ibarra and Elias offered contrasting paths: reform and revolution. Their internal conflicts mirrored the struggle within the Filipino psyche. Sisa’s madness symbolized the breaking point of colonial cruelty. Cabesang Tales embodied the desperation produced by systemic injustice.

Rizal did not merely write stories; he wrote a diagnosis of a wounded society. His novels became forbidden texts eagerly copied and passed from hand to hand. Wherever the Noli and Fili traveled, conversations about justice, identity, and freedom followed. Without these novels, the emotional and intellectual groundwork for revolution would have been far weaker.

Influence on the Propaganda Movement

Rizal’s essays in La Solidaridad expanded on the themes he introduced in his novels. Through articulate, evidence-based arguments, he exposed abuses not as isolated cases but as symptoms of a dysfunctional colonial system.

He argued for representation in the Cortes, equality under the law, secularization of parishes, and educational reform.

He emphasized the importance of civic virtue, explaining that meaningful change required moral and intellectual preparation.

The Propaganda Movement was not a failure; it was a necessary stage. It sharpened the political consciousness of ilustrados, introduced Filipinos to modern political ideas, and allowed Rizal’s arguments to permeate the elite circles that would later play major roles in the Revolution.

Even as Spain ignored these appeals, the movement laid the foundation for a shift from reform to armed resistance — a transition shaped by Rizal’s moral and intellectual leadership.

How the Katipunan Interpreted Rizal

Bonifacio considered Rizal the symbolic leader of the Philippine Revolution. Katipunan ceremonies featured his portrait, treating him as the embodiment of the nation’s spirit. Rizal’s ideas validated the struggle for independence because they revealed the moral bankruptcy of colonial rule.

While Bonifacio admired Rizal’s peaceful approach, he also recognized the limits of reform when faced with an unyielding regime. For Bonifacio, Rizal lit the torch; the Katipunan carried it into battle.

Even Katipuneros who could not read the novels knew Rizal’s reputation: a brilliant Filipino who unveiled colonial cruelty and dared to imagine a nation deserving of freedom.

His symbolic authority was so great that the Katipunan initially hoped to rescue him from exile in Dapitan, believing that the Revolution needed his leadership. Rizal refused because he understood the Revolution was not yet ready. Still, his absence in battle never diminished his influence. It strengthened it.

Rizal’s Reformist Vision and Its Impact on Revolutionary Ideals

Rizal believed that freedom without preparation could lead to chaos. While the Katipunan pursued immediate independence, they embraced many of the values that Rizal emphasized:

- Nationhood rooted in education

- Leadership grounded in morality

- Resistance without cruelty

- Justice as the Revolution’s ultimate goal

Thus, even though the Revolution became violent, it was not fueled by hatred. It was fueled by dignity — the dignity Rizal taught Filipinos to claim.

Aguinaldo, Mabini, and other revolutionary leaders repeatedly acknowledged Rizal’s ideas when shaping the direction of the new republic. Mabini’s political philosophy, in particular, was deeply influenced by Rizal’s emphasis on ethical governance and civic virtue.

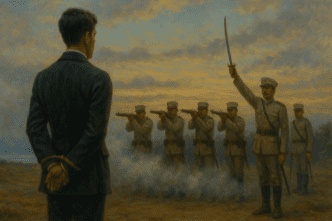

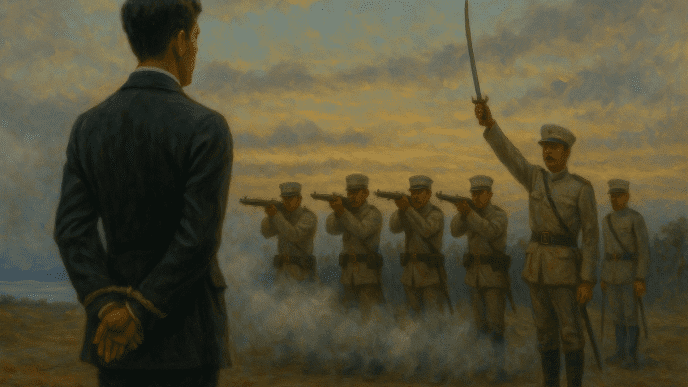

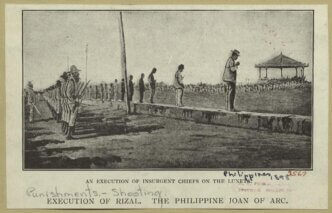

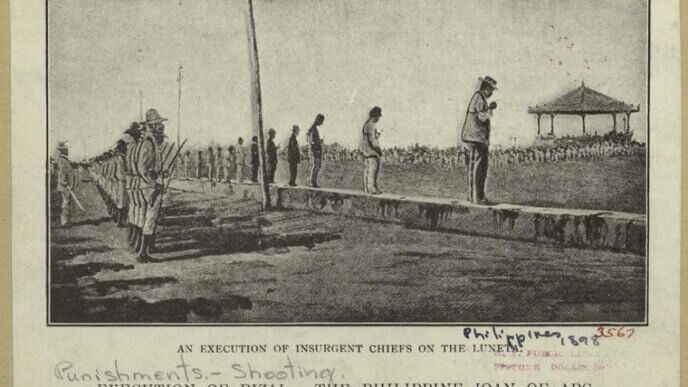

Martyrdom: The Spark That Ignited the Revolution

Rizal’s execution on December 30, 1896, served as the emotional turning point of the Revolution. Spain believed executing him would intimidate Filipinos. The opposite happened. His martyrdom united a country still wrestling with internal divisions.

His final poem, Mi Último Adiós, became a testament of love for the nation, transforming personal sacrifice into a national symbol. His dignified acceptance of death showed Filipinos the moral high ground of their struggle.

After his execution:

- Revolutionary fervor intensified

- Neutral Filipinos joined the uprising

- Existing military fronts strengthened

- Rizal’s name became a battle cry

His death was not merely mourned — it was mobilizing.

Why Rizal Became the Moral Core of the Revolution

Rizal represented something larger than political ideology. He symbolized the Filipino dream of a nation built on justice, education, and moral integrity. His influence endured because he:

- Critiqued oppression without advocating hatred

- Loved his country without demanding reward

- Suffered injustice with clarity and dignity

- Died not as a partisan but as a Filipino

At a time when revolutions around the world often descended into revenge or ideological extremism, Rizal reminded Filipinos that the fight for freedom was also a fight for character.

Long-Term Influence on the Revolutionary Legacy

The Revolution did not end with the Treaty of Paris or American occupation. Its meaning continued to evolve, shaped by Rizal’s legacy. His writings remain central to Philippine education because they provide the ethical foundation for civic life. His reforms guide political discourse. His example inspires generations to confront injustice with intellect and courage.

The Revolution left a blueprint for resistance. Rizal provided the blueprint for nationhood.

Conclusion

Rizal’s influence on the Philippine Revolution cannot be confined to the question of whether he supported armed struggle. His true impact lies in awakening national consciousness, shaping the movement’s moral compass, inspiring its leaders, and giving the Revolution a soul.

He proved that ideas are more powerful than weapons, and that a single life, lived with integrity, can ignite the transformation of an entire nation.