Quick Summary

Rizal did not lead the Philippine Revolution on the battlefield, but his writings, ideals, and moral authority shaped its direction and inspired the very people who carried it out. His execution transformed him from reformist intellectual to national martyr, igniting a revolution that would no longer be delayed.

Introduction

Rizal’s role in the Philippine Revolution is often misunderstood. He neither formed armies nor commanded battles, and he repeatedly distanced himself from violent uprisings that he believed the country was not yet prepared to win. Yet despite this caution, his influence became the Revolution’s deepest foundation. His novels awakened national consciousness, his public campaigns exposed colonial abuses, and his martyrdom united Filipinos across regions, classes, and political beliefs.

While Andres Bonifacio and the Katipunan built the armed movement, it was Rizal who provided the moral and ideological spark. His calls for dignity, education, and civic responsibility shaped the values of a new nation struggling to be born.

The Intellectual Roots of Revolution

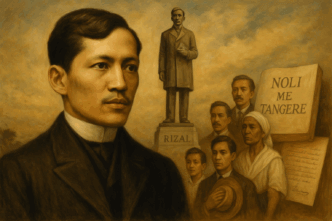

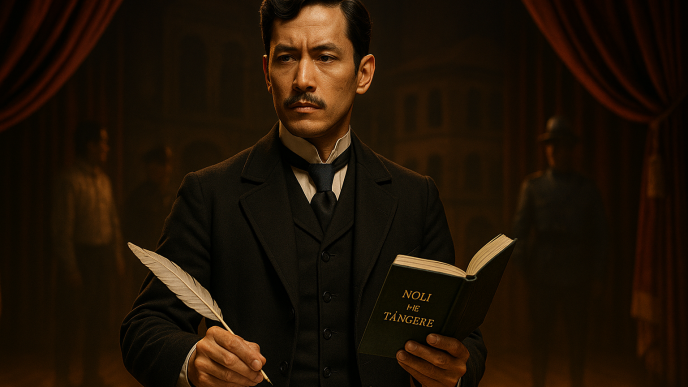

Decades before the Philippine Revolution erupted, Rizal had already begun shaping the ideas that would fuel it. His novels Noli Me Tangere and El Filibusterismo painted a vivid picture of colonial injustice and the urgent need for reform. Though written as art, they functioned as political commentary that unveiled abuses of friars, corruption in the bureaucracy, and the suffering of ordinary Filipinos.

These works circulated widely despite censorship. They awakened sentiments that had long been unspoken. Young professionals, students, farmers, and local elites began to imagine a Philippines capable of self-governance. The language of freedom and dignity that would later define the Katipunan had its origins in Rizal’s pen.

His essays in La Solidaridad further deepened this influence. By arguing for representation, civil liberties, and educational reforms, he created a political vocabulary that helped Filipinos articulate what they wanted their nation to become.

Why Rizal Opposed an Early Revolution

Although Rizal criticized Spanish abuses, he did not initially support a premature uprising. He believed the Philippines lacked weapons, unified leadership, and international recognition. For him, an ill-prepared revolt would lead only to mass suffering without achieving lasting change.

His vision was a gradual transformation: an educated population capable of demanding rights through peaceful, sustained civic effort. This stance often placed him at odds with more radical groups, including the Katipunan.

However, his refusal to endorse immediate rebellion did not mean he was indifferent. He wanted a revolution that was strategic rather than impulsive, one that would succeed rather than self-destruct.

How the Katipunan Viewed Rizal

To the Katipunan, Rizal was the embodiment of the Filipino struggle. Andres Bonifacio, who co-founded the movement, regarded Rizal as the nation’s leading mind and moral guide. Chapters of the Katipunan displayed his portrait in their initiation rites. His ideas were treated almost as sacred doctrine.

Though Rizal did not join the Katipunan and even discouraged its early plans, the group continued to see him as the symbolic head of their cause. His writings gave emotional weight and intellectual clarity to what the Katipuneros sought to achieve through arms.

Rizal’s Arrest and the Revolution’s Timing

When the Revolution was discovered in August 1896, Spanish authorities blamed Rizal as its mastermind despite the lack of evidence. His arrest in Dapitan and subsequent imprisonment in Manila displayed the colonial government’s fear of his influence.

Rizal, then en route to serve as a volunteer doctor in Cuba, was brought back to Manila under suspicion of treason. For the revolutionaries, this injustice confirmed everything he had written about Spanish oppression.

The Katipunan fought passionately to rescue him, but the events unfolded too quickly. His trial was swift, the verdict predetermined.

A Martyr’s Death and a Nation’s Awakening

Rizal’s execution on December 30, 1896, marked the turning point of the Revolution. His final walk through Bagumbayan became a moment of collective awakening. The peaceful man who had called for reforms was condemned as a traitor, revealing a colonial system incapable of fair judgment.

His death ignited widespread anger. Provincial leaders who had been hesitant joined the struggle. Families who had remained neutral now supported the uprising. Even those who disagreed with rebellion began to question Spain’s legitimacy.

Rizal’s final words in Mi Último Adiós symbolized sacrifice, love of country, and unbroken hope. This message strengthened the resolve of those fighting in the field and those organizing the movement’s future direction.

Rizal as the Revolution’s Moral Compass

Rizal’s ultimate legacy lies not in strategic decisions but in the moral framework he provided. He envisioned a nation rooted in education, civic virtue, and justice. Revolutionary leaders used these principles to guide their actions, from forming new governments to rallying their men in battle.

Even Emilio Aguinaldo later recognized that although Rizal did not take up arms, he shaped the Revolution’s soul. His martyrdom unified a fragmented movement and transformed what could have been a regional uprising into a national struggle.

Conclusion

Rizal’s role in the Philippine Revolution was profound and indispensable, though not military in nature. He awakened Filipino identity through literature and civic advocacy. His life showed the power of intellect, while his death exposed the brutality of colonial rule and hardened the nation’s resolve to fight for independence.

He was not the Revolution’s general but its conscience. Not its strategist but its guiding light. In the end, the uprising that he once feared might fail was strengthened by his ideas and sanctified by his sacrifice.