Quick Summary

Throughout his life, Rizal championed peaceful reforms rooted in education, civic responsibility, and equality. Yet the refusal of the colonial government to embrace these changes pushed Filipinos toward open resistance, proving that reform and revolution were intertwined forces shaping the nation’s awakening.

Introduction

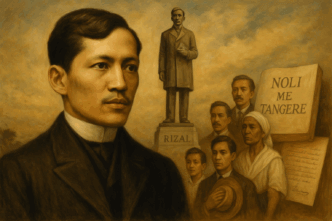

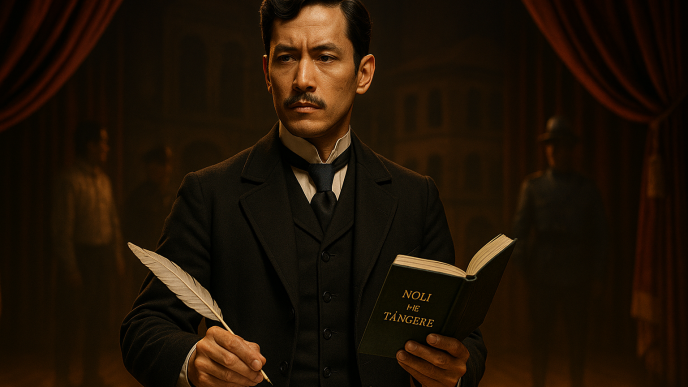

The story of reform and resistance in the late nineteenth century Philippines cannot be told without understanding the central role Rizal played. His writings, advocacy, and public life called for rational and just reforms that could uplift Filipino dignity. But he also witnessed how these peaceful appeals repeatedly collided with a colonial system that protected privilege more than it valued progress.

The tension between reform and resistance defined the path toward nationhood: one vision aimed to transform society through enlightenment, while the other emerged from the realization that peaceful demands were no longer enough. Rizal’s life stood at the heart of this struggle, shaping both the reformist movement and the revolutionary spirit that followed.

The Reformist Vision

Rizal believed that lasting change could be achieved by empowering Filipinos through education and civic participation. He wanted Filipinos to think critically, demand fairness, and engage openly with ideas that shaped the modern world. His essays in La Solidaridad pressed for political representation, equal treatment before the law, and freedom of speech and assembly.

He imagined a society where progress grew from knowledge and reason. The Philippines, in his view, could achieve autonomy only if its citizens were educated, united, and morally grounded. Reform was not merely political for him; it was cultural and intellectual, a long-term transformation of conscience.

Barriers to Reform

The Spanish colonial structure resisted these reformist ideals. Friar authorities held vast economic and political power, and many officials saw education as a threat rather than a path to development. Proposals for representation in the Spanish Cortes were ignored. Calls for secularization were dismissed. Grievances from towns like Calamba were met not with change but with punishment.

This environment convinced many Filipinos that peaceful reform had limits. While Rizal maintained hope that reason could triumph, the reality around him showed that the colonial government was barely willing to consider even the most modest adjustments.

Rising Frustration Among Filipinos

As the gap widened between reformist ideals and oppressive realities, frustration began to take root among Filipinos. Young professionals, farmers, and laborers increasingly felt that submitting petitions and writing essays would not be enough to alter the colonial order.

The Cavite Mutiny of 1872 and the execution of Gomburza lingered as symbols of what happened to those who challenged authority. By the 1890s, economic hardship, racial discrimination, and arbitrary persecution contributed to a climate where resistance grew naturally from desperation.

Even those who admired Rizal’s reformist approach began to question whether the colonial government was capable of genuine change.

Rizal’s Influence on Both Reform and Revolution

Rizal’s writings became a bridge between two movements. His novels exposed injustices that peaceful reform alone could not remedy. Characters like Elias represented those who saw violence as a necessary response to systemic oppression. Meanwhile, characters like Ibarra embodied reformist ideals struggling to survive in a society resistant to progress.

Rizal never openly endorsed armed rebellion, yet his work awakened the very consciousness that made resistance possible. The Katipunan drew strength from his ideas, believing that his call for dignity gave moral legitimacy to their struggle.

Thus, even as Rizal advocated for reforms, his influence helped shape a movement that took a different path.

Why Reform Gave Way to Resistance

The failure of the colonial government to respond to Filipinos’ peaceful demands gradually led to a shift in national sentiment. As more injustices accumulated, reform lost its appeal. Many Filipinos concluded that Spain would never grant equality unless forced to do so.

The discovery of the Katipunan in 1896 proved how deeply resistance had taken root. What began as a small, secret organization turned into a mass movement because people had lost faith in the colonial system’s willingness to change.

Rizal, who feared the consequences of a premature uprising, recognized that resistance was the result of decades of unaddressed oppression.

Reform as a Foundation for Resistance

Although the Revolution erupted through armed struggle, it was built on ideas first articulated in the reform movement. The vision of a free, educated, and self-respecting Filipino people originated from reformist thinkers like Rizal.

Even revolutionary leaders invoked those ideals. Bonifacio admired Rizal’s intellect; Mabini built his political philosophy on the idea of moral and civic responsibility; Aguinaldo recognized that the Revolution needed the inspiration of Rizal’s sacrifice.

Thus, reform and resistance were not opposing ideas but stages of the same national journey. Reform planted the seeds. Resistance made them flower.

Conclusion

Rizal’s pursuit of reforms revealed both the possibilities and limits of peaceful change in a colonial society resistant to equality. When those reforms were denied, a stronger movement for resistance emerged. Together, these forces shaped the birth of the Philippine nation.

Rizal illuminated the path toward justice with ideas, and when the time came, Filipinos carried those ideals forward through action. Reform gave the nation its vision. Resistance gave it momentum.