Quick Summary

The Philippines during Rizal’s lifetime lived under a rigid colonial system dominated not only by the Spanish civil government but, more significantly, by the Catholic friar orders. Society was shaped by race, class, limited education, censorship, and heavy economic burdens. This world profoundly influenced Rizal’s growing awareness and reformist vision.

Introduction

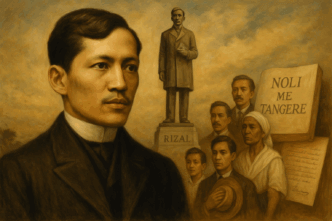

To understand Jose Rizal’s ideas and the reforms he advocated, one must return to the Philippines of the nineteenth century. This was a society where colonial authority shaped almost every aspect of daily life, from schools and parishes to land ownership and even one’s personal identity. While fiestas, markets, and local traditions continued, they existed alongside structures of power that privileged a few and weakened the many.

Rizal grew up observing this world, quietly noticing patterns of abuse, discrimination, and injustice long before he could put them into words. Over time, the realities of Spanish rule would form the backbone of his novels and essays, each a careful attempt to describe the long shadow of colonial rule and to point toward a more dignified future.

The Colonial Government and the Limits of Power

The Spanish colonial government in the Philippines appeared formidable, yet beneath the surface it was riddled with contradictions. The governor-general served as the King of Spain’s representative, holding executive, military, and judicial authority. On paper, his power extended throughout the islands, but in practice he often found his decisions weakened by political rivalries and the overwhelming influence of the friar orders.

Throughout the provinces, the alcalde mayor acted as judge, administrator, and tax collector. This combination of roles frequently led to corruption, with many alcaldes engaging in illicit trade or forcing locals to sell goods at unfair prices. Their ability to dispense justice while also profiting from commercial ventures placed ordinary Filipinos at a clear disadvantage.

At the local level, gobernadorcillos and cabezas de barangay worked as intermediaries between the colonial state and Filipino communities. Though they enjoyed certain privileges, their authority was often symbolic, since they were expected to obey both government officials and the friars. Their role required delicate diplomacy; too much independence could provoke retaliation, but too much subservience could alienate the people they served.

The Dominance of the Friars

The most powerful figures in many towns were not government officials but the Catholic friars. Their influence extended into nearly every part of daily life. They controlled parishes, supervised elementary schools, managed local records, and acted as informal advisers to high-ranking officials. Their authority came not only from religious office but from long-standing networks of land ownership and economic wealth.

The friars owned large haciendas, especially in provinces like Laguna, Cavite, and Bulacan. Tenant farmers paid rent that could rise at any time, and disputes were often settled in favor of the friars regardless of evidence. Families such as the Mercados of Calamba experienced firsthand how friar landlords could evict entire communities, a trauma that left a lasting imprint on Rizal.

Beyond land and education, the friars also influenced marriages, burials, community festivals, and local leadership appointments. Their power was cultural and political, but also personal, shaping the attitudes and behaviors of people from birth to death.

A Rigid and Unequal Social Structure

Spanish colonial society was organized according to race, birthplace, and class. At the top were the peninsulares, Spaniards born in Spain who occupied the highest positions and enjoyed extensive privilege. Insulares, Spaniards born in the Philippines, ranked below them yet still held many administrative and commercial roles.

Below these were the mestizos — Spanish, Chinese, or mixed ancestry — who often prospered, especially in trade and education. Many members of the ilustrado class, including Rizal, came from this group. Their exposure to both Filipino culture and European ideas gave them a unique vantage point.

The largest and least privileged group were the indios, the native Filipinos. They carried the heaviest economic burdens, had limited legal protections, and were prevented from occupying positions of influence. Their daily lives revolved around farming, small-scale trade, and community obligations. Despite this, their resilience and cultural traditions formed the heart of local society.

The principalia, composed of local elites, served as a bridge between the colonial government and Filipino communities. While they enjoyed exemptions and prestige, their position was precarious. They remained subject to the whims of friars and officials, and their power was far from independent.

Education: Limited, Religious, and Controlled

Education during Rizal’s youth was shaped by the needs of colonial authority. Schools taught basic literacy and religious doctrine but avoided subjects that encouraged questioning or independent thought. Advanced education was possible in Manila, yet even universities were shaped by ecclesiastical influence.

Young students learned by memorization rather than understanding. Scientific and philosophical education was confined, and access to books was limited. The colonial government feared unrestricted knowledge, believing it could spark political unrest.

This restrictive system pushed Rizal and many ilustrados to pursue education in Europe. There, they encountered liberal ideas, scientific methods, and political writings that broadened their understanding and sharpened their critique of colonial rule.

Economic Hardships and Colonial Policies

Life under Spanish rule was marked by economic burdens that affected every social class except the elite. Tribute taxes, land rent, forced labor, and multiple fees made survival difficult for ordinary families. Polo y servicio required Filipino men to work on public projects for weeks at a time, often leaving their farms unattended and their families struggling.

Certain industries were controlled through monopolies, such as the tobacco monopoly, which forced Filipinos to grow, process, and sell tobacco under strict regulations. These policies enriched Spanish officials but trapped farmers in cycles of debt.

Friar estates further complicated the economy. Many Filipino farmers cultivated land they did not own, always vulnerable to rent hikes and eviction. Land disputes were often dismissed in favor of the friars, deepening frustration among tenants.

These economic hardships were not merely material concerns. They shaped the worldview of Filipinos, revealing how deeply the colonial system influenced their survival and dignity.

Religion and Social Life

Religion shaped Filipino life from birth to death. Baptism, marriage, and burial all required interaction with the parish priest. While faith itself was sincere, the administration of sacraments was often tied to financial cost or social compliance. Poor families struggled to afford religious rites, and certain individuals were denied rites for political or personal reasons.

The friars were guardians of morality, but their authority also enabled abuses—coercion, favoritism, and intrusion into private life. Confession, meant to be a spiritual practice, sometimes became a method of surveillance.

Rizal recognized the importance of faith but criticized its use as a tool of exploitation. His novels portrayed both compassionate priests and abusive ones, reflecting the moral complexity of colonial religious life.

Censorship and Control of Thought

Under Spanish rule, ideas were dangerous. Books were censored, newspapers regulated, and private letters opened without permission. Topics that questioned colonial authority, especially loyalty to the friars or the Crown, were forbidden.

This environment made genuine intellectual exchange difficult. Even university lectures were monitored. Discussions of politics, equality, or liberal thought were often suppressed.

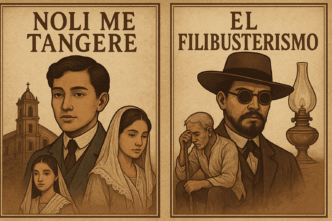

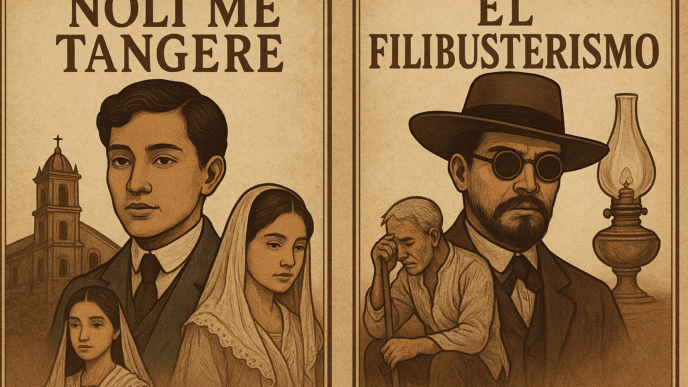

When Rizal’s Noli Me Tangere arrived in the Philippines, the reaction was swift and severe. The novel was condemned for exposing societal injustices. Its existence alone demonstrated the power of ideas to challenge authority.

The Rise of National Consciousness

In the 1880s, a generation of young Filipinos began traveling to Spain and other parts of Europe for education. There, they encountered new ways of thinking about government, human rights, and citizenship. They saw societies where public debate was encouraged and newspapers openly criticized leadership.

These ilustrados formed the Propaganda Movement, using essays, speeches, poetry, and journalism to advocate for reforms. They did not initially seek independence but equality: representation in the Cortes, freedom of speech, secularization of parishes, and protection under the law.

Rizal’s work became central to this movement. Through literature and reasoned critique, he exposed the weaknesses of colonial rule and helped Filipinos imagine a more just society.

Toward Revolution

While Rizal believed reform was possible, many Filipinos lost hope in peaceful change. The execution of Fathers Gómez, Burgos, and Zamora in 1872 revealed the harshness of colonial justice. The eviction of tenant families, the abuse of power by friars, and the refusal of Spain to grant reforms pushed Filipinos toward resistance.

Organizations like the Katipunan emerged, inspired partly by Rizal’s writings but moving beyond his reformist approach. They sought independence, believing that no colonial power could truly protect Filipino dignity.

Rizal’s influence remained crucial. Even in advocating peaceful reform, he helped awaken a generation that would later seek complete freedom.

Conclusion

The Philippines during Rizal’s lifetime was a colony shaped by a complex mix of authority, faith, oppression, and resilience. Spanish rule created structures that restricted movement, controlled ideas, and limited economic freedom. Yet within this harsh environment grew minds like Rizal’s—curious, critical, and committed to justice.

Understanding this society allows us to understand the urgency behind Rizal’s writings. He was not simply describing injustice—he was confronting the world that shaped him, hoping that a more enlightened nation could emerge. His life and works remain enduring reflections of a time when Filipinos began to recognize both the weight of colonial rule and the possibility of liberation.