When José Rizal came of age in the 19th century, the Philippines was undergoing subtle but profound changes. Spanish rule had long dictated the nation’s political and religious life, and education served as one of its most powerful tools of control.

Yet, in this same system, seeds of awakening were quietly planted. The century saw a slow transition from rote religious instruction to an emerging sense of intellectual pursuit — a shift that would produce the ilustrados, the educated class that gave rise to reformists like Rizal himself.

Education Under Religious Orders

For much of the Spanish period, education in the Philippines was dominated by the Catholic Church. The friars managed nearly every school, from the smallest village classroom to the oldest university. Their goal was not to foster independent thinking but to inculcate obedience and piety. Lessons centered on Christian doctrine, prayers, catechism, and basic literacy, often taught in Spanish or Latin — languages foreign to most Filipinos.

The colonial government provided little oversight. Education was not a right but a privilege, often restricted to the children of the principalia or those favored by the clergy. In rural areas, access was scarce; in towns and cities, it was heavily influenced by the local parish priest. As a result, education reinforced the social hierarchy rather than challenged it.

Primary and Secondary Schooling

By the early 19th century, Spain began to modernize its colonial administration. The 1863 Educational Decree — a landmark reform — established the first government-supported public education system in the Philippines. It mandated that every town should have at least one primary school for boys and another for girls, with free instruction in reading, writing, arithmetic, Spanish, and Christian morals. It also created normal schools for teacher training, supervised by the Jesuits.

In theory, this decree represented progress. In practice, however, implementation was uneven. Many schools lacked teachers, textbooks, and facilities. The friars still retained authority over local education, especially in rural communities. Despite these limitations, the decree marked the beginning of a new era: literacy rates slowly improved, and more Filipinos gained access to formal learning.

Higher Education and the Universities

For those who could afford it, Manila offered several institutions of higher learning. The most prominent were the University of Santo Tomas, run by the Dominicans, and the Colegio de San Juan de Letran, managed by the same order. The Jesuits, after their return to the Philippines in 1859, founded the Ateneo Municipal de Manila, where Rizal would study. These schools catered primarily to the elite and followed European-style curricula emphasizing Latin, philosophy, theology, and the humanities.

While these universities were impressive by colonial standards, they also served to maintain orthodoxy. The teaching of liberal ideas, science, or political economy was discouraged. Nonetheless, exposure to classical studies and scholastic logic developed in students a sense of intellectual discipline — something that thinkers like Rizal later expanded upon when they studied abroad.

The Birth of the Ilustrado Class

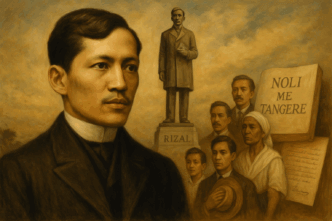

The latter half of the 19th century witnessed the rise of the ilustrados, educated Filipinos who became the intellectual vanguard of reform. Many of them, including Rizal, Marcelo H. del Pilar, and Graciano López Jaena, were products of local schools who pursued further education in Europe. There they encountered the liberal philosophies of the Enlightenment and the nationalist movements sweeping the continent.

This exposure transformed their understanding of identity and justice. They began to see the contradictions of a colonial system that preached civilization while denying equality. Education became their instrument for change. Through writings, newspapers, and organizations like La Solidaridad, the ilustrados challenged Spain to practice the principles it claimed to uphold.

Women and Education

The education of women in the 19th century was limited but gradually improving. The 1863 Educational Decree formally recognized the need for girls’ schools, a remarkable step for its time. Girls were taught reading, writing, arithmetic, and religion — but also domestic skills like sewing and cooking, reflecting the era’s gender norms.

Private institutions, such as the Colegio de Santa Isabel and the Beaterio de Santa Catalina, offered education to upper-class girls, often preparing them for religious life. A few women, like Rizal’s sisters and his mother, Teodora Alonso, displayed intellectual ability that defied social expectations. Teodora herself, educated and principled, became one of Rizal’s earliest teachers, instilling in him both moral discipline and a love for learning.

Obstacles to Progress

Despite reforms, the 19th-century education system remained deeply flawed. Access was limited, teaching methods were outdated, and instruction often relied on memorization rather than reasoning. The use of Spanish as the medium of instruction excluded most Filipinos, and very few learned it fluently. Moreover, the Church’s control of education stifled intellectual freedom and censored ideas perceived as “dangerous” or “liberal.”

Corruption also plagued the system. Many teachers were underpaid or unqualified, and resources were scarce. Rural schools sometimes existed only on paper, their funds diverted by officials. These issues reflected a larger colonial pattern: education was designed to maintain order, not empowerment.

Education as a Catalyst for Nationalism

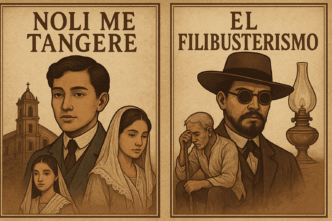

Yet, paradoxically, it was through this limited education that Filipino nationalism began to take shape. Those who studied — especially abroad — learned to think critically about their place in the empire. Rizal’s exposure to European universities and scientific study opened his eyes to the inequality of colonial rule. His novels Noli Me Tangere and El Filibusterismo both depict the hypocrisy of a society where education was restricted by fear and faith rather than guided by truth and progress.

By the late 19th century, schools had become battlegrounds of ideology. The Spanish authorities sought to preserve loyalty, while reformists viewed education as the path to liberation. This tension culminated in the intellectual awakening that preceded the Philippine Revolution.

Conclusion

Education in the 19th-century Philippines was both a chain and a key — a means of control and an instrument of awakening. Though dominated by the Church and constrained by colonial policy, it gradually fostered a generation capable of questioning authority and imagining freedom. From the small town classrooms of Calamba to the lecture halls of Europe, the story of Rizal’s education mirrors that of his country: nurtured under oppression, enlightened by learning, and transformed by the pursuit of truth.