Quick Summary

Religion shaped nearly every aspect of Filipino life in the 19th century. Catholic rituals, fiestas, devotions, and everyday practices influenced community identity, social structure, and personal spirituality during José Rizal’s time.

Introduction

In the 19th century, religion formed the spiritual and cultural backbone of Filipino life. Catholicism, introduced centuries earlier by Spanish missionaries, had become deeply woven into community traditions, family routines, and personal identity.

By Rizal’s era, faith was not only a set of beliefs but also a daily experience expressed through rituals, celebrations, and social customs. Understanding this religious world is essential to understanding how Filipinos lived, worked, and found meaning during the final decades of colonial rule.

The Central Role of Catholicism

Catholicism dominated religious life across the archipelago, shaping both public celebrations and private devotions. Churches stood at the heart of towns, serving as spiritual centers, social spaces, and symbols of colonial authority. Faith guided everything from prayer and moral instruction to community gatherings and political ceremonies.

For many Filipinos, religious identity offered comfort amid hardship and a sense of belonging in a changing world.

Daily Devotions and Personal Prayer

Everyday spirituality was marked by simple yet meaningful practices. Families prayed before meals, recited evening novenas, and displayed images of saints in their homes. The rosary was central to evening routines, and many households participated in nightly or weekly prayer circles. These practices created a rhythm of reflection and faith that anchored family life, helping individuals navigate daily challenges.

Attending Mass

Sunday Mass was one of the most important weekly rituals. Townspeople dressed in their best clothes and walked to the parish church, often gathering on the plaza before and after the service. The ceremony blended solemnity with social connection: families reunited, neighbors exchanged news, and young people met potential partners. Mass attendance was not only a sign of piety but also evidence of social participation, reinforcing a shared sense of community.

The Influence of the Parish Priest

The parish priest held significant authority, often serving as spiritual leader, educator, counselor, and community figure. Priests baptized children, officiated weddings, heard confessions, and guided moral instruction. In many towns, they also managed schools, supervised festivals, and shaped local customs. This influence extended beyond religion, affecting education, governance, and even family relationships. Though personalities varied widely, the priest’s presence was a constant force in daily life.

Feasts, Processions, and Fiestas

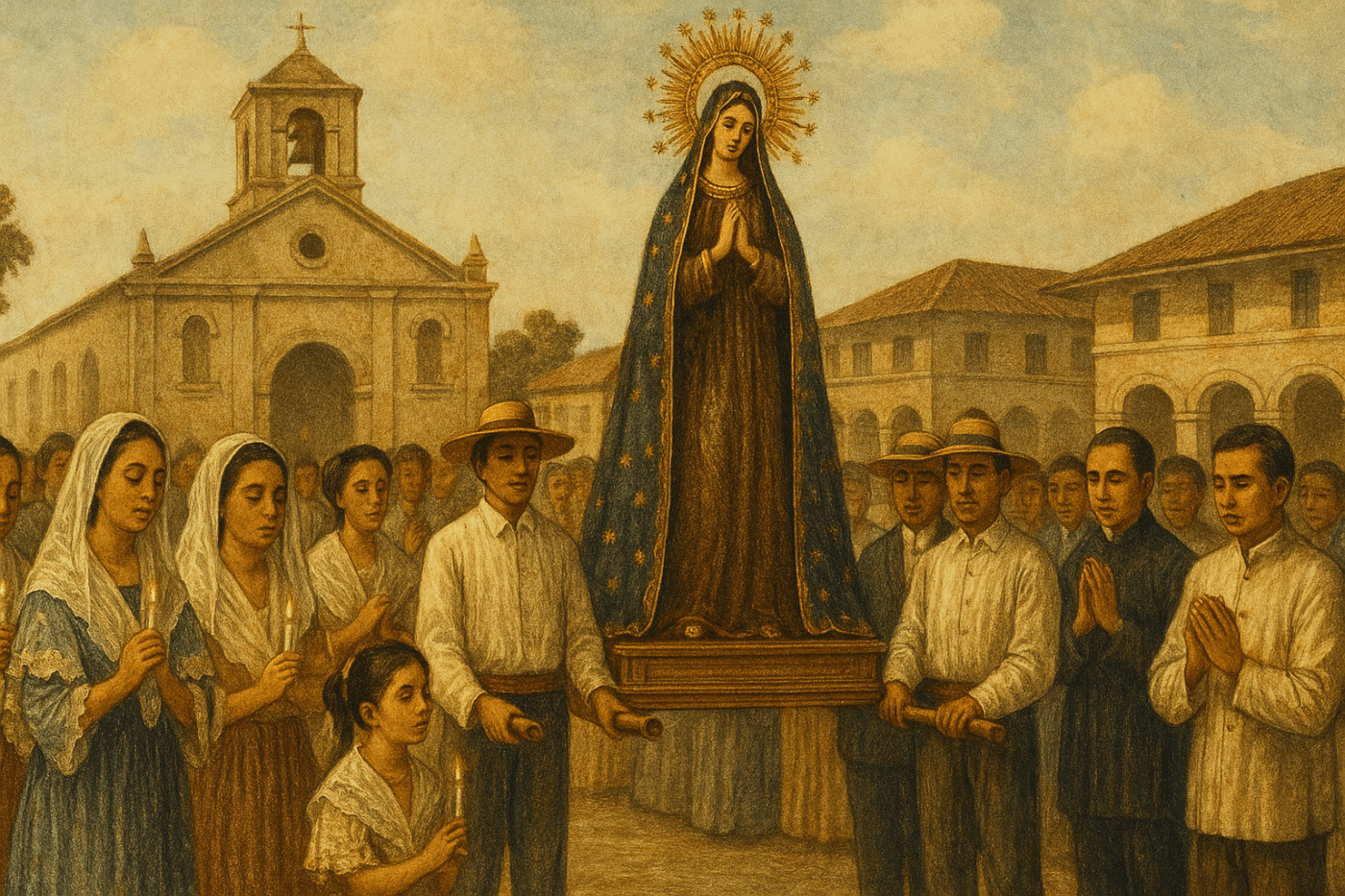

Religious fiestas were among the most anticipated events each year. These celebrations honored patron saints through Masses, processions, music, theater, and communal feasts. Streets filled with lanterns, flowers, and banners, transforming towns into vibrant centers of activity. Processions with images of saints carried on platforms moved through streets accompanied by prayers, chanting, and music. Fiestas brought people together from nearby barangays, strengthening community ties and marking the rhythm of the calendar.

Major Liturgical Seasons

Catholic seasons shaped the flow of the year. Lent brought solemnity, fasting, and the staging of pabasa chants and Passion plays. Holy Week was especially significant, with processions dramatizing Christ’s suffering and death. Christmas blended Spanish influences with local Filipino customs, filling parishes with music and candlelight. These seasons gave structure to time, connecting community life with sacred tradition.

Belief in Saints and Patronage

Filipinos developed strong devotion to saints, treating them as protectors, intercessors, and companions in daily life. Each town had a patron saint whose feast day was celebrated with pride. Individuals formed special attachments to figures like San Roque, San Isidro Labrador, or the Virgin Mary, depending on their needs or livelihoods. Devotees prayed for good harvests, healing, safe travel, or family guidance, believing deeply in the power of intercession.

Religious Brotherhoods and Women’s Societies

Confraternities and women’s devotional groups played a significant role in religious life. These organizations organized processions, maintained altars, cared for church decorations, and assisted during major feasts. Membership fostered community service, discipline, and spiritual commitment. Through these groups, many Filipinos—especially women—exercised leadership within their religious communities.

Home Altars and Sacred Space

Most Filipino homes contained a simple altar featuring candles, flowers, and religious images. These household shrines were places for evening prayer, thanksgiving, and special petitions. Families gathered around them during illness, storms, or important decisions. Home altars reflected the blending of faith and daily routines, offering an accessible and intimate space for devotion.

Blending Indigenous Beliefs and Catholic Practice

Although Catholicism dominated, many pre-colonial beliefs quietly persisted. Communities blended traditional healing practices, superstitions, and local rituals with Catholic teachings. Some sought help from albularyos or folk healers while also praying novenas; others combined indigenous symbols with Christian ceremonies. This blending created a uniquely Filipino expression of faith that was both ancient and new, rooted in tradition yet shaped by colonial influence.

Religion as a Social Force

Religious life also served social and cultural functions. Baptisms, weddings, and funerals involved extended families and reinforced kinship ties. Fiestas encouraged unity, cooperation, and generosity. Participation in church activities helped define one’s reputation, especially within the principalia class. For many, religious involvement signaled respectability, moral standing, and community pride.

The Presence of Other Religious Communities

Though Catholicism was dominant, other religious groups existed in 19th-century Philippines. Muslim communities in the south maintained their own traditions, while Chinese immigrants often blended Confucian, Buddhist, and ancestral practices. Protestant ideas occasionally circulated through foreign merchants and travelers, though they remained limited. These diverse practices contributed to a complex landscape of belief alongside Catholic dominance.

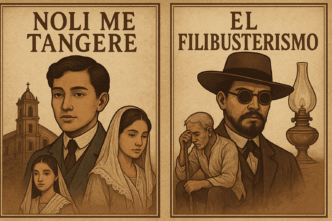

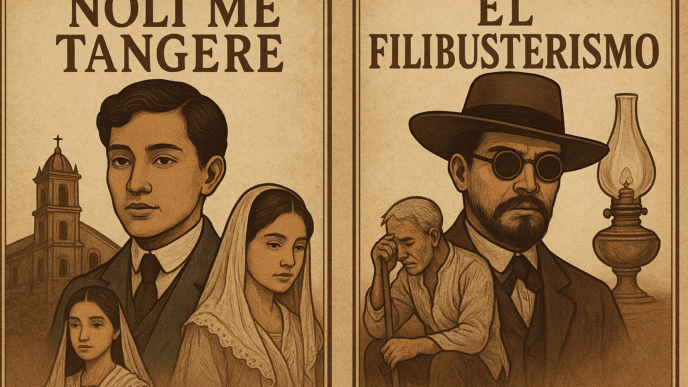

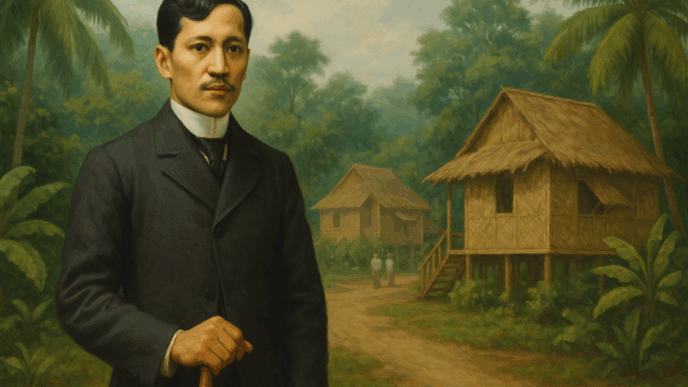

Religion and Rizal’s World

Religious practice shaped the world Rizal grew up in and profoundly influenced his experiences. His schooling, family life, and community interactions were grounded in Catholic traditions. Many scenes in Noli Me Tangere and El Filibusterismo reflect the rituals, customs, and complexities he observed. For Filipinos of his generation, religion was not merely a doctrine but a lived culture that shaped thought, behavior, and identity.

Conclusion

Religion in 19th-century Filipino life was a vibrant blend of devotion, tradition, and communal identity. It structured the rhythms of daily life, guided celebrations, and shaped values across generations. Understanding these practices provides rich insight into the society that influenced José Rizal, revealing a world where faith was both a personal compass and a collective bond. Through rituals, festivals, and everyday prayer, Filipinos found strength, meaning, and belonging in a rapidly changing colonial landscape.