Quick Summary

“Alianza Íntima Entre La Religión Y La Educación” (“The Intimate Alliance Between Religion and Education”) is one of Jose Rizal’s most thoughtful poems, exploring how faith and learning must work together to enrich both the individual and the life of a nation. Written in Spanish during his years of study, it reflects a young Rizal already thinking deeply about the moral foundations of society.

Background

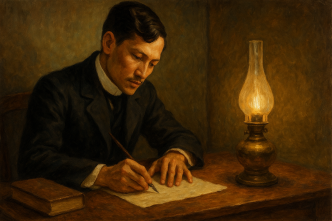

Jose Rizal wrote “Alianza Íntima Entre La Religión Y La Educación” early in his intellectual life, during a period when he was developing both his moral convictions and his ideas about nationhood. The poem first appeared during his school years in Manila, a time when education in the Philippines was dominated by religious institutions. Rizal, who admired the scholarly Jesuits but also saw the injustices committed by friars, was already wrestling with the complex relationship between faith and learning.

This poem offers a glimpse of Rizal before the revolutionary fire of Noli Me Tangere and El Filibusterismo—a young scholar trying to reconcile spirituality, virtue, and intellectual growth. His early environment demonstrated both the strengths and the failings of the religious educational system: faith could uplift the soul, but dogma, when misused, could suffocate inquiry. Rizal believed that neither religion nor education should exist in isolation. For him, true progress required the merging of moral guidance and enlightened understanding.

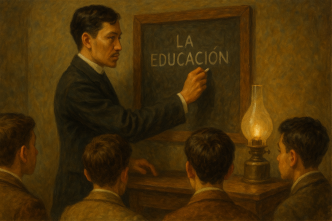

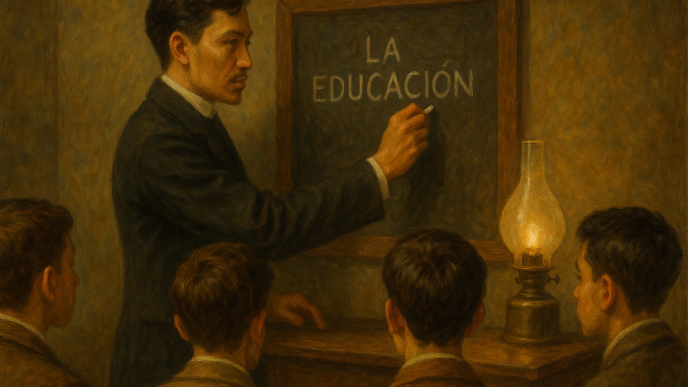

The Spain-ruled Philippines of his time was a place where education often served to reinforce authority rather than cultivate critical thought. Rizal’s poem quietly challenges that structure. While respectful of religion’s role, he argues for an education that elevates conscience rather than blinds it.

Full Poem: Alianza Íntima Entre La Religión Y La Educación

Cual hiedra trepadora

Tortuosa camina

Por el olmo empinado,

Siendo entrambos encanto al verde prado,

Y a la par se embelecen

Mientras unidos crecen;

Y si el olmo compasivo faltase,

La hiedraal carecer de su Consuelo

Vería tristemente marchitarse;

Tal la Educación estrecha alianza

Con alma Religión une sincera;

Por ella Educación renombre alcanza;

Y ¡ay! Del ser que ciegao desechando

De santa Religión sabias doctrinas,

De su puro raudal huye nefando.

Si de la vid pomposa

El tallo ufano crece

Y sus dulces racimos nos ofrece,

En tanto que al sarmiento generosa

Alimenta la planta cariñosa;

Tal límpidas Corrientes

De célica virtud dan nueva vida

A Educación cumplida,

Guiándola con sus luces refulgentes;

Por ella delicado olar exhale,

Y Sus frutos sabrosos nos regala.

Sin Religión, la Educación humana

Es cual nave del viento combatida

Que pierde su timón en lucha horrible

Al fragoroso impulse y sacudida

Del proceloso Bóreas terrible

Que la combate fiero

Hasta undirla altanero

En los abismos de la mar airada.

Si el rocío del cielo

Vigoriza y sustenta a la pradera,

Y por él, en Hermosa primavera,

Salen las flores a border el suelo;

Tal si a la Educación fecundizara

Con sus doctrinas Religión piadosa,

Hacia el bien lacentera caminara

Con planta generosa;

Y dando de virtud lozanas flores

Esparciera doquiera sus olores.

Analysis

Though brief and gentle in tone, the poem contains ideas that would mature and deepen throughout Rizal’s life.

First, he presents religion as warmth — the moral fire that shapes character, guides conscience, and provides a vision of goodness. Second, he frames education as light — the illumination that reveals truth, cultivates reason, and frees the mind from ignorance. Rizal insists that neither is complete without the other. Warmth without light can lead to blind zeal. Light without warmth can produce cold intellect without humanity.

At the time Rizal wrote this piece, the tension between religious authority and the emerging ideals of scientific education was growing. Many Filipinos saw European enlightenment thinking as a way to challenge colonial oppression, while friar institutions feared losing their influence. The poem offers a third path: unity. Rizal imagines a partnership in which moral values shape learning, and learning purifies and uplifts faith.

What is most striking is that even in his youth, Rizal already sensed the dangers of imbalance. When religion stands without education, moral understanding becomes vulnerable to manipulation. When education stands without religion — or without a grounding moral compass — it risks becoming detached from compassion.

Rizal’s later works show how this early idea grew more complex. In his novels, he depicts friars who abuse religious authority and teachers who suppress inquiry. Yet even then, he never abandoned the idea that moral integrity and intellectual clarity must coexist. “Alianza Íntima” is, in many ways, the philosophical seed of that belief.

This poem also reveals Rizal’s long-term educational vision for the Philippines. He dreamed of a nation where schools would cultivate both virtue and knowledge, producing citizens capable of leadership, critical thought, and ethical action. He viewed education as a tool for liberation, but liberation grounded in responsibility.

More than a century later, the poem remains relevant. In an age of rapid technological change, misinformation, cultural tension, and shifting values, Rizal’s call for harmony between moral purpose and intellectual clarity speaks with renewed urgency. He reminds readers that education without conscience is dangerous, and faith without understanding is incomplete.

“Alianza Íntima Entre La Religión Y La Educación” is a brief poem, but it captures a lifelong truth in Rizal’s philosophy: a nation rises not by knowledge alone, nor by devotion alone, but by the union of both.