Quick Summary

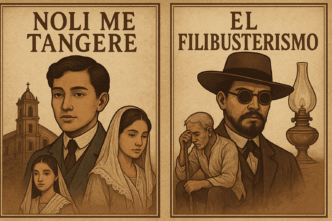

Noli Me Tangere and El Filibusterismo are twin novels that shaped Filipino nationalism. The Noli exposes social injustices with hope for peaceful reform, while the Fili presents a darker, more radical vision shaped by disillusionment. Together, they reveal Rizal’s evolving political thought and provide a complete portrait of colonial society’s struggles, failures, and the forces that pushed the nation toward revolution.

Introduction

Noli Me Tangere (1887) and El Filibusterismo (1891) stand as the twin pillars of Filipino nationalism. They are not sequels in the ordinary sense — they are two halves of a profound moral, political, and psychological portrait of colonial society. Together, they capture the birth of Filipino consciousness, the depth of colonial injustice, and the evolution of one man’s struggle for his nation’s soul. Yet they differ significantly in tone, theme, structure, and purpose.

A close comparison reveals how these novels mirror Rizal’s intellectual journey from hope to despair, from reformism to radical disillusionment, and from faith in peaceful change to a haunting acknowledgment of revolution’s inevitability.

Historical Context

Noli Me Tangere was written during a period when Rizal still believed in the possibility of peaceful reform. Europe was alive with liberal ideas, and the Propaganda Movement was gaining momentum. Hope existed — however fragile — that Spain might listen.

By the time El Filibusterismo was written, those hopes had collapsed. The execution of Gomburza, the exile of Filipino intellectuals, the persecution of Rizal’s family in Calamba, and the refusal of the government to acknowledge reformist pleas hardened Rizal’s worldview. The Fili is a product of a darker, more turbulent historical moment.

Thus, the differing emotional tones of the novels mirror the evolution of Rizal’s political experience.

Tone and Mood

The most striking contrast between the two novels lies in their tone.

Noli Me Tangere is a story of beginnings — a novel of awakening. Its tone oscillates between satire, romance, gentle humor, and social critique. Even in its darkest scenes, it contains hope that enlightenment can transform society. The young, idealistic Crisóstomo Ibarra embodies the belief that progress can emerge from education, civic participation, and reasoned discourse.

El Filibusterismo, on the other hand, is steeped in bitterness. Its tone is somber, cynical, and almost suffocating. The novel abandons the hopeful reformism of the Noli and confronts the reality that peaceful appeals to justice have failed. Simoun, the transformed Ibarra, carries with him a fury born from betrayal and despair.

If the Noli is a sunrise, the Fili is the long shadow cast by a dying sun.

Central Characters and Their Evolution

Crisóstomo Ibarra serves as the narrative link between the two novels.

In Noli Me Tangere, he is a young, idealistic reformist returning from Europe with dreams of improving the Philippines through education and social progress. His character embodies optimism, rationality, and the belief that political change can come from within the system.

In El Filibusterismo, Ibarra returns in disguise as Simoun — a wealthy jeweler who hides his identity behind a beard, glasses, and a plan for violent revolution. Simoun is no longer a reformist but a man consumed by vengeance. He believes that only destruction can cleanse society of its deep corruption.

This transformation is symbolic: the failure of reforms can give birth to radicalism. Rizal warns that oppression breeds desperation, and desperation creates revolutionaries.

Other characters show similar contrasts:

- Maria Clara in the Noli represents hope, purity, and romance. In the Fili, she becomes a symbol of despair, trapped in the convent and eventually dying — a metaphor for the Philippines’ lost innocence.

- Sisa, Basilio, and Crispin represent the suffering of ordinary Filipinos in the Noli. In the Fili, Basilio has grown into a young man pursuing education but ultimately drawn into the revolutionary turmoil.

- Elias, the noble rebel of the Noli, foreshadows the ideology of the Fili. His death signals that idealistic reform may fail, and more radical solutions may arise.

Themes and Philosophical Direction

Noli Me Tangere emphasizes the possibility of peaceful reform. Its themes include education, moral awakening, social injustice, and the need for enlightenment. The novel critiques friar abuses, corruption, and the cruelty of the colonial system, but it does so with the belief that reforms could heal society.

El Filibusterismo explores darker themes: the corruption of power, the futility of reform, the seduction of revenge, and the inevitability of revolution when justice is denied. Its philosophical direction is more radical — not because Rizal endorses violence, but because he illustrates how oppression pushes people toward it.

The message of the Fili is almost prophetic: if injustice continues, revolution will erupt, regardless of whether it is guided by wisdom or vengeance.

Satire vs. Political Allegory

Noli Me Tangere relies heavily on satire. Its humorous scenes — Doña Victorina’s absurd vanity, the buffoonery of friars, the comical pretensions of local officials — expose the ridiculousness of colonial society. Humor becomes a weapon that disarms and educates.

El Filibusterismo abandons humor almost entirely. Its narrative is tighter, darker, and more symbolic. The lamp that Simoun plans to use to spark a bombing is more than a plot device — it is an allegory of explosive social tension. The student movement, Cabesang Tales’ tragedy, and Basilio’s internal struggle all reflect forces pushing society toward violent upheaval.

Where the Noli critiques, the Fili warns.

Treatment of Religion

In the Noli, Rizal critiques religious hypocrisy but still portrays faith as a potential source of compassion and moral strength. Characters like Padre Florentino later embody this positive spiritual influence.

In the Fili, the critique becomes harsher. Religion is manipulated as a tool of oppression, and the people’s faith is weaponized against them. The novel reveals how institutional religion can deform a society’s conscience when controlled by corrupt authority.

Structure and Narrative Energy

Noli Me Tangere reads like a traditional realist novel with interwoven storylines, community portraiture, and character exploration. It portrays a Philippine society in full detail, from fiestas to courtroom scenes to personal dramas. Its narrative is expansive and panoramic.

El Filibusterismo is more focused and compact. It is structured almost like a political thriller. Every event pushes the reader toward the climactic explosion that Simoun plans. The pacing is tighter, the scenes more charged, and the emotional landscape darker.

Depiction of Society

The Noli shows colonial society as a community with potential for growth if enlightened leadership emerges. It offers a cross-section of Philippine life — from the wealthy to the oppressed, from educated reformists to simple farmers — suggesting that change is possible.

The Fili portrays society as nearing collapse. Corruption is more entrenched, reforms have failed, and despair has hardened hearts. This shift mirrors Rizal’s growing realization that Spanish authorities would not grant justice voluntarily.

Rizal’s Message: Reform vs. Revolution

Noli Me Tangere advocates for peaceful reform. Rizal uses the novel to call for education, dialogue, and moral awakening. He believed that an enlightened citizenry could transform society without violence.

El Filibusterismo, although it dramatizes a violent plot, ultimately rejects revolutionary vengeance. Simoun’s plan fails, and his dying confession to Padre Florentino reveals Rizal’s position: a revolution fueled by hatred is doomed. True freedom must arise from justice, wisdom, and moral responsibility.

The Fili demonstrates the consequences of pushing a people to the brink. Rizal does not glorify revolution, but he warns that oppression plants its seeds.

Conclusion

Noli Me Tangere and El Filibusterismo are companion works that chart the evolution of a nation’s awakening. One begins with hope, the other with heartbreak. Together, they form a complete narrative of a society searching for its identity, its dignity, and its path to liberation.

The Noli reveals what is wrong with the Philippines. The Fili reveals what happens when those wrongs are left unaddressed.

Reading them together helps Filipinos understand not only the roots of colonial injustice but also the moral and political foundations of their struggle for freedom. They continue to shape the nation because their truths — about power, corruption, courage, and compassion — remain deeply relevant today.