Quick Summary

Rizal’s trial was a carefully staged political drama designed to silence the most influential Filipino reformist of his time. His execution on December 30, 1896, turned him into a national martyr and ignited even greater resistance against Spanish colonial rule.

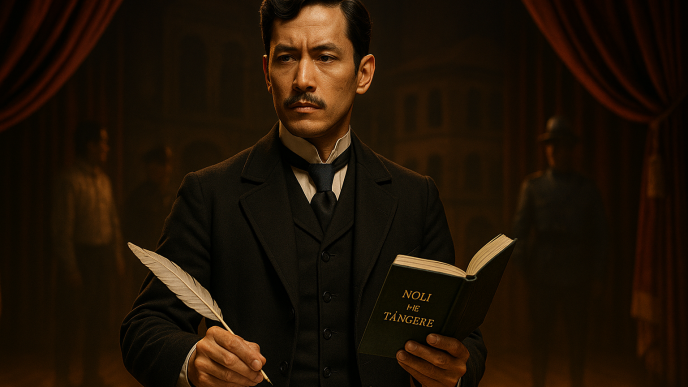

Introduction

Rizal’s final days reveal the Spanish colonial government’s desperation to crush the growing spirit of nationalism. Although he neither led an armed rebellion nor organized a military uprising, he became the symbolic target of the state.

His trial and execution were not simply legal proceedings but acts of political theater meant to intimidate Filipinos into submission. Instead, the opposite happened: his death awakened the nation.

Arrest After the Katipunan Uprising

By mid-1896, the Propaganda Movement had been weakened, and the Katipunan was rapidly gaining members. When the Spanish authorities uncovered the secret society, they responded with sweeping arrests. Rizal, who had been living a quiet life in Dapitan, was already on his way to Cuba as a volunteer doctor. He hoped to serve in a humanitarian capacity and distance himself from the tensions in Manila.

Yet before he could reach Cuba, he was detained in Barcelona and shipped back to the Philippines. To the colonial authorities, it was convenient to link him to the newly discovered revolutionary group. Although no evidence tied him to the Katipunan’s plans, his influence on Filipino consciousness made him their prime suspect.

A Predetermined Trial

Rizal arrived in Manila on November 3, 1896. He was imprisoned in Fort Santiago, where he was subjected to constant surveillance and interrogations. His trial was set before a military court, a forum that already ensured a biased and hasty judgment.

The charges were grave: rebellion, sedition, and forming illegal associations. The prosecution argued that his writings had inspired the Katipunan and therefore made him morally responsible for the uprising. Despite the lack of concrete proof, the mere existence of his novels and essays was treated as incriminating evidence.

Rizal defended himself eloquently. He denied involvement in the rebellion, emphasizing that he advocated peaceful reforms and believed the country was not ready for a violent confrontation. He insisted that he had never met the leaders of the Katipunan and that his vision for change did not align with the organization’s methods.

Still, the outcome was predetermined. The government needed a scapegoat to justify its severe crackdown, and Rizal was the most powerful symbol they could eliminate.

Public Pressure and Political Anxiety

The Spanish authorities faced mounting anxiety. The Revolution had already erupted in several provinces. Towns were rising in defiance, and Spanish troops were struggling to maintain control. Executing Rizal was seen as a way to break the revolutionaries’ morale.

At the same time, moderates and reformists pleaded for clemency. Even some Spaniards recognized that killing a peaceful reformer would provoke outrage. But Governor-General Camilo de Polavieja, newly appointed and determined to restore order through force, signed the death warrant.

For the government, executing Rizal was a political strategy. For Filipinos, it would become the turning point of their struggle.

Rizal’s Last Night

On the night before his execution, Rizal displayed calmness that astonished even his jailers. He wrote farewell letters, including his final poem Mi Último Adiós, which he hid inside an alcohol stove. He met with family members one last time, embracing them despite their anguish. He forgave his executioners and prayed for his country.

That evening, he also wrote a letter to his friend Ferdinand Blumentritt, assuring him that he was at peace with his fate. Throughout these moments, he showed the same clarity of purpose that defined his entire life: he wanted his sacrifice to inspire unity, dignity, and a renewed commitment to the Filipino cause.

The Walk to Bagumbayan

At dawn on December 30, 1896, Rizal was escorted from his cell to Bagumbayan Field, now Rizal Park. He walked with dignity, refusing to be tied at the elbows as condemned prisoners usually were. The Spanish firing squad faced him with solemn readiness.

Rizal requested to face his executioners, a final act of courage that authorities denied. They insisted he stand with his back to the firing line. As the shots rang out, he managed to twist his body so that he fell facing the rising sun. The moment became one of the most iconic in Philippine history.

His death was witnessed by a crowd, many holding back tears. What the colonial government intended as a warning instead became a spark of national awakening.

Impact on the Revolution

News of his execution spread rapidly. Revolutionaries fought harder, enraged that a peaceful reformist was executed as a traitor. Those who had doubted the movement now joined it. Provincial uprisings intensified, and Rizal’s death became a rallying cry for resistance.

His martyrdom transformed him from a critic of abuses into the moral pillar of the nationalist cause. Even those who disagreed with armed revolt could no longer ignore the depth of injustice imposed by colonial rule.

Legacy of His Trial and Execution

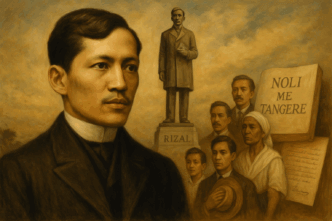

Rizal’s trial was a historic miscarriage of justice. It illustrated the inability of colonial authorities to tolerate dissent and their fear of intellectual movements. Yet his death also forged a national identity rooted in sacrifice, education, and moral courage.

Every year, December 30 is celebrated as Rizal Day, not merely to remember his final moments but to reflect on the ideals he lived for. His execution marked the birth of a united Filipino consciousness and opened the path toward eventual independence.

Conclusion

Rizal’s trial and execution were meant to extinguish the growing desire for freedom. Instead, they amplified it. His calm acceptance of death, his unwavering belief in the Filipino people, and his refusal to abandon his principles turned him into the national hero whose ideas and sacrifice shaped the destiny of a nation.