Background

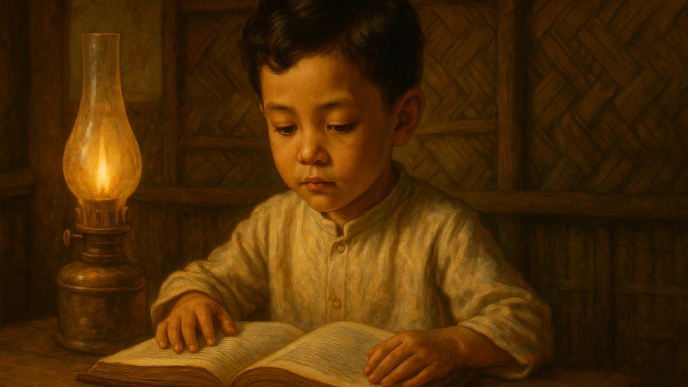

José Rizal wrote My Retreat (originally Mi Retiro) during his exile in Dapitan between 1892 and 1896. It was composed at the request of his mother, Doña Teodora Alonso, who longed to hear her son express his inner peace and reflections while living far from home. By this time, Rizal had withdrawn from political activism and embraced a quieter life shaped by teaching, healing, farming, and scientific work.

Dapitan offered him an unexpected calm. Surrounded by the sea, forests, and mountains, Rizal rediscovered nature and the quiet rhythms of rural life. My Retreat is a product of this environment. It reveals a gentle, contemplative Rizal whose mind moves between contentment and longing, memory and realization, solitude and spiritual grounding.

The poem captures the heart of his exile: the forced stillness that allowed him to rediscover a part of himself he had lost during the years of travel, conflict, and struggle.

To explore Rizal’s original Spanish text, you may read our full coverage of Mi Retiro, including the complete poem and its literary context.

The Full Poem: My Retreat (Mi Retiro)

Beside a spacious beach of fine and delicate sand

and at the foot of a mountain greener than a leaf,

I planted my humble hut beneath a pleasant orchard,

seeking in the still serenity of the woods

repose to my intellect and silence to my grief.

Its roof is fragile nipa; its floor is brittle bamboo;

its beams and posts are rough as rough-hewn wood can be;

of no worth, it is certain, is my rustic cabin;

but on the lap of the eternal mount it slumbers

and night and day is lulled by the crooning of the sea.

The overflowing brook, that from the shadowy jungle

descends between huge bolders, washes it with its spray,

donating a current of water through makeshift bamboo pipes

that in the silent night is melody and music

and crystalline nectar in the noon heat of the day.

If the sky is serene, meekly flows the spring,

strumming on its invisible zither unceasingly;

but come the time of the rains, and an impetuous torrent

spills over rocks and chasms—hoarse, foaming and aboil—

to hurl itself with a frenzied roaring toward the sea.

The barking of the dog, the twittering of the birds,

the hoarse voice of the kalaw are all that I hear;

there is no boastful man, no nuisance of a neighbor

to impose himself on my mind or to disturb my passage;

only the forests and the sea do I have near.

The sea, the sea is everything! Its sovereign mass

brings to me atoms of a myriad faraway lands;

its bright smile animates me in the limpid mornings;

and when at the end of day my faith has proven futile,

my heart echoes the sound of its sorrow on the sands.

At night it is a mystery! … Its diaphanous element

is carpeted with thousands and thousands of lights that climb;

the wandering breeze is cool, the firmament is brilliant,

the waves narrate with many a sigh to the mild wind

histories that were lost in the dark night of time.

‘Tis said they tell of the first morning on the earth,

of the first kiss with which the sun inflamed her breast,

when multitudes of beings materialized from nothing

to populate the abyss and the overhanging summits

and all the places where that quickening kiss was pressed.

But when the winds rage in the darkness of the night

and the unquiet waves commence their agony,

across the air move cries that terrify the spirit,

a chorus of voices praying, a lamentation that seems

to come from those who, long ago, drowned in the sea.

Then do the mountain ranges on high reverberate;

the trees stir far and wide, by a fit of trembling seized;

the cattle moan; the dark depths of the forest resound;

their spirits say that they are on their way to the plain,

summoned by the dead to a mortuary feast.

The wild night hisses, hisses, confused and terrifying;

one sees the sea afire with flames of green and blue;

but calm is re-established with the approach of dawning

and forthwith an intrepid little fishing vessel

begins to navigate the weary waves anew.

So pass the days of my life in my obscure retreat;

cast out of the world where once I dwelt: such is my rare

good fortune; and Providence be praised for my condition:

a disregarded pebble that craves nothing but moss

to hide from all the treasure that in myself I bear.

I live with the remembrance of those that I have loved

and hear their names still spoken, who haunt my memory;

some already are dead, others have long forgotten—

but what does it matter? I live remembering the past

and no one can ever take the past away from me.

It is my faithful friend that never turns against me,

that cheers my spirit when my spirit’s a lonesome wraith,

that in my sleepless nights keeps watch with me and prays

with me, and shares with me my exile and my cabin,

and, when all doubt, alone infuses me with faith.

Faith do I have, and I believe the day will shine

when the Idea shall defeat brute force as well;

and after the struggle and the lingering agony

a voice more eloquent and happier than my own

will then know how to utter victory’s canticle.

I see the heavens shining, as flawless and refulgent

as in the days that saw my first illusions start;

I feel the same breeze kissing my autumnal brow,

the same that once enkindled my fervent enthusiasm

and turned the blood ebullient within my youthful heart.

Across the fields and rivers of my native town

perhaps has traveled the breeze that now I breathe by chance;

perhaps it will give back to me what once I gave it:

the sighs and kisses of a person idolized

and the sweet secrets of a virginal romance.

On seeing the same moon, as silvery as before,

I feel within me the ancient melancholy revive;

a thousand memories of love and vows awaken:

a patio, an azotea, a beach, a leafy bower;

silences and sighs, and blushes of delight …

A butterfly athirst for radiances and colors,

dreaming of other skies and of a larger strife,

I left, scarcely a youth, my land and my affections,

and vagrant everywhere, with no qualms, with no terrors,

squandered in foreign lands the April of my life.

And afterwards, when I desired, a weary swallow,

to go back to the nest of those for whom I care,

suddenly fiercely roared a violent hurricane

and I found my wings broken, my dwelling place demolished,

faith now sold to others, and ruins everywhere.

Hurled upon a rock of the country I adore;

the future ruined; no home, no health to bring me cheer;

you come to me anew, dreams of rose and gold,

of my entire existence the solitary treasure,

convictions of a youth that was healthy and sincere.

No more are you, like once, full of fire and life,

offering a thousand crowns to immortality;

somewhat serious I find you; and yet your face beloved,

if now no longer as merry, if now no longer as vivid,

now bear the superscription of fidelity.

You offer me, O illusions, the cup of consolation;

you come to reawaken the years of youthful mirth;

hurricane, I thank you; winds of heaven, I thank you

that in good hour suspended by uncertain flight

to bring me down to the bosom of my native earth.

Beside a spacious beach of fine and delicate sand

and at the foot of a mountain greener than a leaf,

I found in my land a refuge under a pleasant orchard,

and in its shadowy forests, serene tranquility,

repose to my intellect and silence to my grief.

English translation by Charles Derbyshire. Public domain.

Analysis

The poem My Retreat offers one of the most intimate views of Rizal’s inner life. It shows a man who has stepped away from public struggle and found a temporary sanctuary in nature. The work reveals several intertwined themes: serenity, resignation, memory, and spiritual renewal.

The opening stanzas present Dapitan as a peaceful refuge framed by sea, sky, and forest. Rizal emphasizes natural imagery not merely for its beauty but for the emotional healing it brings. The waves, wind, and birds all create an atmosphere of calm, suggesting that nature gives him what the political world has taken away. Exile, though imposed, becomes a space for self-restoration.

Midway through the poem, the tone shifts subtly toward reflection and loss. Rizal recalls his youthful energy and idealism, now softened by years of conflict, separation, and disappointment. The metaphor of a fallen petal captures his sense of distance from the passionate zeal of his earlier life. Yet the poem does not sink into despair. Even as he recounts faded dreams, Rizal finds new strength in quiet simplicity.

The theme of faith also emerges strongly. Though he declares himself broken by destiny, he insists that a deeper belief endures — a faith not tied to institutions but to personal conviction. This resilience transforms exile into a period of spiritual maturation. Dapitan becomes not just a physical retreat but an inward journey toward acceptance and clarity.

The closing stanzas elevate solitude into a maternal figure. For Rizal, solitude is not loneliness but comfort, nurturing him like a mother cradling a tired child. This final image reveals the poem’s emotional core: in the stillness of Dapitan, he finds peace, not through escape but through reconciliation with his circumstances.

My Retreat stands as a poetic record of Rizal’s most reflective years. It shows him stripped of the public role he once carried, returning to the essentials of life — nature, peace, memory, and contemplation. Far from being a poem of surrender, it is one of renewal, marking the calm before the decisive final chapter of his life.