Quick Summary

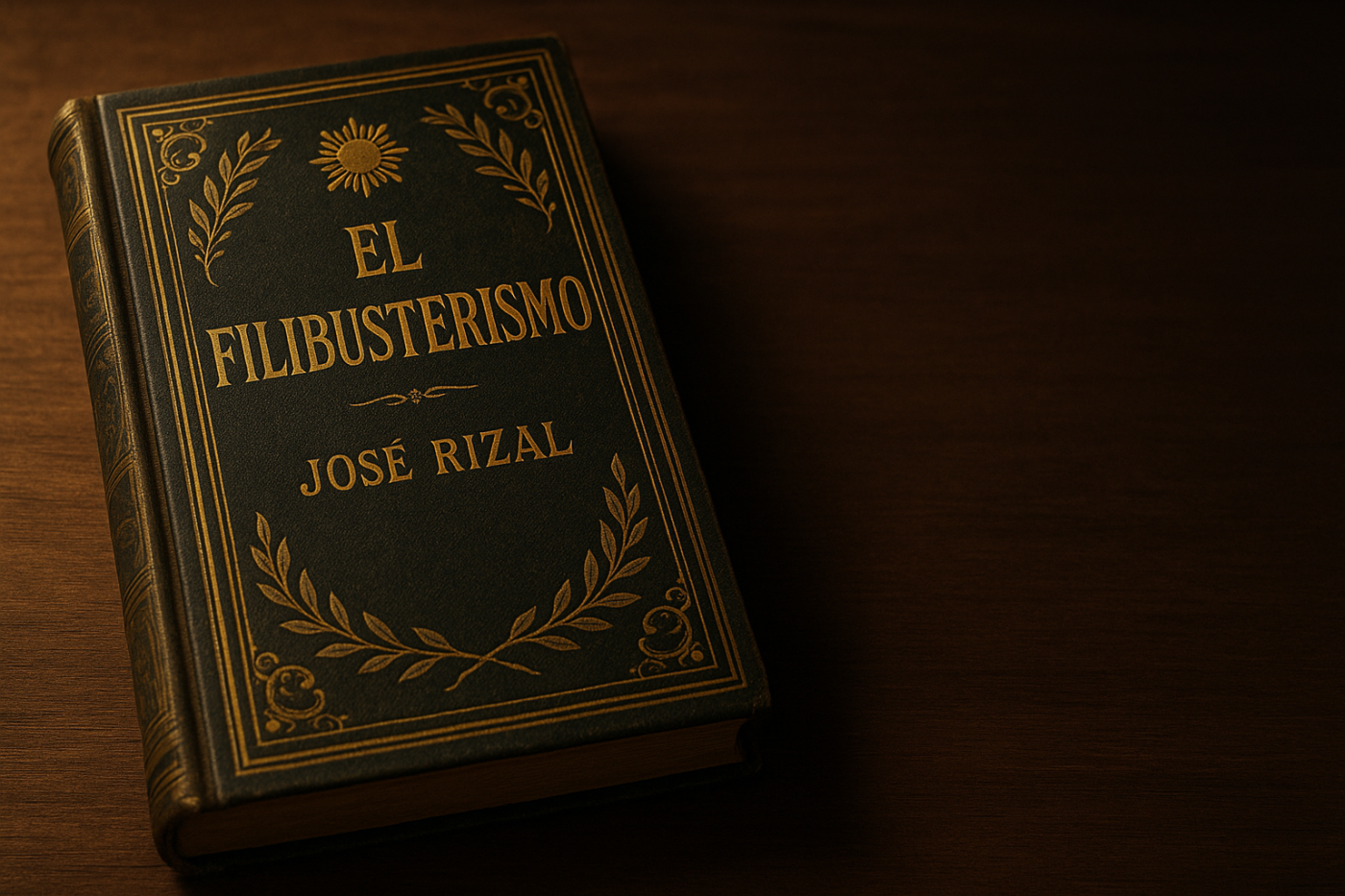

El Filibusterismo (The Reign of Greed) is Jose Rizal’s bleak, radical sequel to Noli Me Tangere. This article gathers 20 powerful quotations from the Charles Derbyshire English translation and unpacks how they expose colonial abuse, corrupted ideals, and Rizal’s growing frustration with both oppressor and oppressed.

Introduction

El Filibusterismo is Jose Rizal’s most searing work: a novel written not with ink alone but with the accumulated grief, urgency, and disillusionment of a people pushed to the edge.

Where Noli Me Tangere carried the idealism of a young reformer appealing to conscience, El Filibusterismo speaks with the voice of a nation forced to confront the harsh truth that change may not come through gentle persuasion. Its characters — students, priests, rebels, and ordinary townsfolk — wrestle with questions that continue to echo through Philippine history: What is justice? What courage is required to face tyranny? What must the youth shoulder to lift a nation from its long sleep?

The following twenty quotations, drawn directly from The Reign of Greed, Charles Derbyshire’s translation of El Filibusterismo, capture the novel’s most striking insights. They reveal the moral debates, emotional tensions, and revolutionary impulses at the heart of Rizal’s work. Each line opens a window into the fears, hopes, and contradictions of a society on the brink.

More than a century later, these words still challenge readers to examine the weight of silence, the cost of obedience, the danger of despair, and the enduring possibility of renewal.

20 Essential Quotes From El Filibusterismo

These are not merely memorable lines. They are the distilled voice of a nation awakening — and the legacy of a writer who understood that literature could become a mirror, a warning, and a call to action all at once.

“You must shake or shatter the vase to spread its perfume, you must smite the rock to get the spark!”

– Padre Florentino, as he speaks to the dying Simoun (Chapter 39, The Last Chapter)

Florentino’s metaphor teaches that suffering and moral struggle produce enlightenment. For Rizal, social transformation is never gentle — friction creates sparks. He offers this not to glorify pain, but to show that comfortable societies rarely awaken. Subjugated people discover their dignity only through trials that break open the “vase” of complacency.

“There is something providential in the persecutions of tyrants, Señor Simoun!”

– Padre Florentino, in continuation of his final speech (Chapter 39)

Rizal suggests that tyranny contains the seeds of its own downfall. Persecution forces a nation to either surrender or finally resist. Spanish cruelty inadvertently forged the Filipino identity. The line feels prophetic, considering Rizal himself later became the victim whose execution would help ignite a revolution.

“Love alone realizes wonderful works, virtue alone can save!”

– Padre Florentino (Chapter 39)

This is Rizal’s rejection of violent revolution. Simoun’s path of revenge collapses because hatred corrupts even noble aims. Rizal’s alternative is moral and intellectual labor — love of country expressed through justice, truth, and sacrifice. True liberation, he insists, cannot be built on terror.

“Our ills we owe to ourselves alone, so let us blame no one.”

– Padre Florentino (Chapter 39)

A painful truth: Filipinos must also confront their complicity in their own suffering — cowardice, apathy, selfishness, and corruption. Rizal doesn’t deny Spanish abuses; he argues that real freedom requires internal reform as well. This line remains one of the most debated in the entire novel.

“Why independence, if the slaves of today will be the tyrants of tomorrow?”

– Padre Florentino (Chapter 39)

Rizal warns against replacing foreign masters with local dictators. Without moral renewal, political independence becomes meaningless. Many readers see this as one of the most important political statements in Philippine literature.

“While a people preserves its language, it preserves the marks of its liberty.”

– Simoun, as he debates with the students about the Spanish language (Chapter 14, A Student’s Dilemma)

For Rizal, language shapes thought. Abandoning one’s native tongue signifies internalized colonial shame. Simoun’s argument is anti-assimilationist: true freedom begins with confidence in one’s linguistic identity.

“Language is the thought of the peoples.”

– Simoun (Chapter 14)

A condensed version of the previous idea. Language is not merely a tool but the vessel of a people’s worldview. Attempts to erase or replace it constitute an attack on national consciousness.

“Some day you will perhaps be a great physician… but greater yet will be he who can inject a new idea into this anemic people!”

– Simoun, as he persuades Basilio (Chapter 7, Simoun)

Simoun belittles Basilio’s personal ambitions, urging him to embrace a larger cause. Rizal criticizes educated elites who pursue private success while ignoring the suffering of the nation. The metaphor of an “anemic people” captures the moral and intellectual starvation caused by colonial rule.

“Where are the youth who will consecrate their golden hours to the welfare of their native land?”

– Padre Florentino (Chapter 39)

One of Rizal’s most famous calls to the youth. After witnessing the failure of Simoun’s rebellion, Florentino appeals to a generation not yet corrupted by power. Rizal sees the youth as the nation’s moral reserve, capable of acting where their elders have faltered.

“The school of suffering tempers; the arena of combat strengthens the soul.”

– Padre Florentino (Chapter 39)

Rizal redefines suffering as a forge. Filipinos learn resilience through adversity. This does not romanticize pain; instead, it shows how oppression creates the conditions for people to discover inner strength.

“I want to be free, to live free!”

– Placido Penitente, after enduring humiliations in school (Chapter 12, Placido Penitente)

A raw cry of frustration. Placido’s struggle reflects Rizal’s critique of the friar-dominated education system, which kills curiosity and dignity. The line captures the universal human desire for freedom from psychological and institutional abuse.

“You strip him and then scoff at his nakedness.”

– Isagani, as he criticizes the friars who mock students they themselves oppress (Chapter 30, The Classroom)

One of Rizal’s fiercest metaphors. Colonial authorities first deny education and rights, then ridicule Filipinos for being “ignorant.” The line exposes the hypocrisy of systems that create inferiority and then blame the victims for it.

“Each youth had lost another hour of his life and with it a portion of his dignity and self-respect.”

– Narrator (Chapter 30)

Rizal’s narrator condemns a school system that humiliates students and rewards memorization over understanding. The line resonates with modern criticisms of oppressive or authoritarian educational environments.

“What are you going to do with Castilian, the few of you who will speak it? Kill off your own originality?”

– Simoun (Chapter 14)

Rizal warns that blind imitation of the colonizer kills cultural authenticity. Colonial education promises advancement but also encourages self-erasure. Simoun exposes the trap: learning Spanish can become a form of internal colonization.

“The vulture was gorging itself with meat… and because the corruption developed slowly, I have stimulated greed.”

– Simoun, as he explains his dark strategy (Chapter 7)

Simoun reveals he has purposefully nurtured corruption to accelerate the system’s collapse. Rizal presents this disturbing strategy to show how vengeance can become morally diseased. It is political nihilism disguised as revolution.

“Now I have returned to destroy that system… even though I may have to shed oceans of tears and blood.”

– Simoun (Chapter 7)

Simoun’s confession marks the novel’s ideological turning point. He abandons reform and embraces destruction. Rizal lets this extremist voice resonate but ultimately shows its failure.

“What are physical sufferings compared to moral tortures? What is the death of a man beside the death of a society?”

– Simoun (Chapter 7)

This line reveals the emotional logic behind Simoun’s radicalism: moral corruption is worse than individual death. Rizal acknowledges the appeal of this argument but also warns that reducing individuals to pawns is dangerous.

“The basis of prestige for colonial governments is the weakest of all, since it depends upon the consent of the governed.”

– Isagani (Chapter 27, The Friars)

Isagani argues that authority based on prestige and intimidation is fragile. Only governments grounded in justice endure. Rizal embeds democratic theory directly into the dialogue.

“He who gives his gold and his life to the State has the right to require of it opportunity better to care for his life.”

– Isagani (Chapter 27)

A proto–social justice argument. If citizens support the State, the State owes them education, dignity, and opportunity. Rizal directly challenges colonial systems that exploit the people while offering nothing in return.

“When there are professors, there will be students.”

– Isagani (Chapter 30)

Isagani counters the friar claim that “students must reform first.” He argues that good teachers produce good students, not the other way around. Rizal reminds us that those with power bear responsibility for the moral tone of the institutions they lead.

Conclusion

These twenty quotes reveal why El Filibusterismo remains one of the most powerful books ever written about colonialism and the human condition. Through Simoun’s fury, Isagani’s idealism, Basilio’s hesitation, Placido’s frustration, and Padre Florentino’s wisdom, Rizal paints a portrait of a nation at the breaking point.

Each line is a window into the Philippines of 1891 — and into enduring truths about power, justice, identity, and responsibility.