Republic Act No. 1425 — popularly known as the Rizal Law — is a 1956 Philippine law that requires all schools, public and private, to teach courses on Jose Rizal’s life, works, and writings, with special attention to his novels Noli Me Tángere and El Filibusterismo. It was signed into law by President Ramon Magsaysay on June 12, 1956.

What the Law Actually Says

RA 1425 has a short but powerful set of provisions. Here’s what they do, translated into everyday terms:

- Make the Rizal Course Mandatory.

Every school must include a subject on Rizal’s life, works, and writings. In college, the unexpurgated versions of Noli and Fili (or their English translations) are to be used as basic texts. The law also empowers the Board of National Education to issue rules to implement this, including primers and readers. - Stock the Library.

All schools must keep an adequate number of Noli, Fili, and other Rizal works and biographies in their libraries; these are to be on the required reading list. - Publish and Translate for Everyone.

The state must ensure Noli, Fili, and other writings are translated into English, Tagalog, and major Philippine languages, printed in cheap editions, and distributed free to readers through local councils. - Protect Freedom of Religion.

Nothing in the law allows religion to be attacked in public schools; and the rules must provide a limited exemption (on religious grounds) from the requirement to read the unexpurgated novels—but not from taking the course itself. - Fund It.

RA 1425 even authorized ₱300,000 (in 1956 pesos) to kickstart printing and distribution.

A Law Born in Debate

The Rizal Bill — pushed in the Senate by Claro M. Recto and Jose P. Laurel — sparked a fierce, highly public debate in 1956. The Catholic Church opposed making the unexpurgated novels compulsory, citing anti-clerical passages; civic groups, veterans of 1896, Freemasons and others rallied to support the bill as a nation-building measure.

A compromise added the religious-conscience exemption noted above; President Magsaysay then signed it on Flag Day, June 12, 1956. Contemporary and later accounts (including the 1956 Philippines Free Press feature and modern summaries) document the players and arguments on both sides.

How It’s Implemented in Schools

- Basic Education (DepEd). A standing DepEd order reiterates that Noli and Fili are required readings in high school (historically 3rd and 4th year), and frames Rizal teaching as a vehicle for nationalism, human rights, and civic virtues. Under K–12, practice commonly places Noli in Grade 9 and Fili in Grade 10.

- Higher Education (CHED/HEIs). In colleges and universities, a three-unit “Life and Works of Rizal” course remains standard as the direct implementation of RA 1425; a 1994 presidential memorandum directed the Education and Higher Education agencies to fully implement the law in all institutions.

Why Filipinos Study Rizal (Beyond “Because It’s the Law”)

The legislative preamble to RA 1425 lays out a timeless rationale that still resonates:

- Nation-Building and Civic Character.

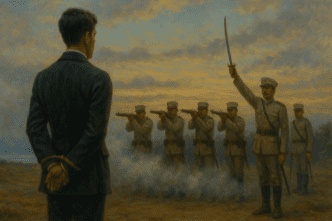

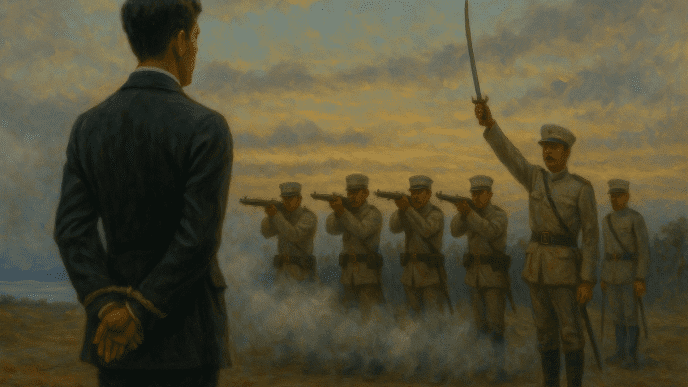

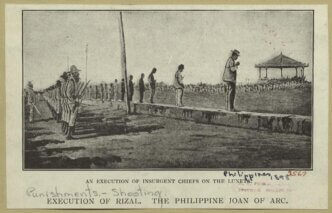

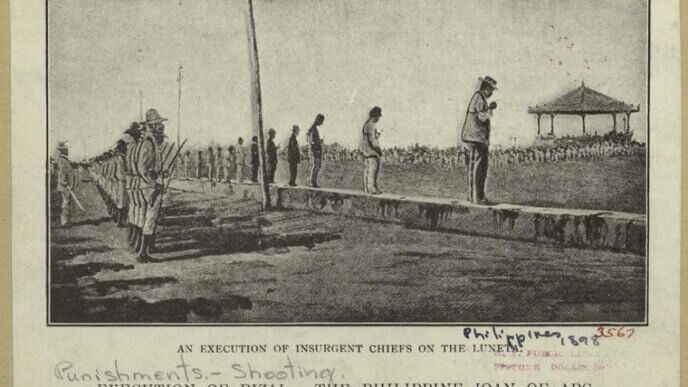

Lawmakers explicitly sought a “re-dedication” to freedom and nationalism, and tasked schools to cultivate moral character, personal discipline, civic conscience, and citizenship—all through a deep engagement with Rizal’s ideas. Noli and Fili were singled out as a “constant and inspiring source of patriotism,” especially for the youth. - Historical Literacy and Anti-Authoritarian Thinking.

Rizal’s works dramatize colonial abuse, corruption, and the perils of unaccountable power. Studying them gives students a historical lens to analyze present-day social issues and to value civil liberties and the rule of law — the exact civic competencies the statute aims to foster. - Shared Cultural Touchstones.

Quotations, characters, and scenes from Noli and Fili populate Philippine public life — from classroom discussions to theater and film — so the novels function as a common cultural language for debating reform, faith, education, and justice. DepEd guidance uses them to animate literature, history, and even arts curricula. - Accessibility by Design.

The law does not only mandate a course; it orders translations, cheap editions, and free distribution so Rizal’s ideas reach all Filipinos, not just college students or Spanish readers. That democratizing intent is unusual in a curricular law—and still relevant today. - Continuing Relevance.

From education reforms to church–state debates, public conversations often recall the 1956 compromise as a precedent for balancing conscience rights with civic education. In this sense, “studying Rizal” doubles as studying how a democracy argues, compromises, and legislates about values.

FAQs

Is reading the unexpurgated novels compulsory for everyone?

In college, the law specifies unexpurgated texts (or their English translations) as basic texts; rules allow religious-conscience exemptions from the unexpurgated reading requirement, but not from taking the subject itself.

Why do some schools teach Noli in Grade 9 and Fili in Grade 10?

That sequencing reflects K–12 curriculum practice; earlier, DepEd required them in the third and fourth years of high school.

Is the law still in force?

Yes. RA 1425 remains law, and national agencies have repeatedly reiterated its implementation.

Key Takeaways

- RA 1425 mandates the study of Rizal in all schools and sets concrete mechanisms: courses, library copies, translations, low-cost editions, and funding.

- It emerged from a historic church–state debate; the final law balances conscience rights with a clear national-civic mission.

- Filipinos study Rizal not only to meet a requirement, but to build historical consciousness, shared civic values, and a common cultural vocabulary for public life.