Quick Summary

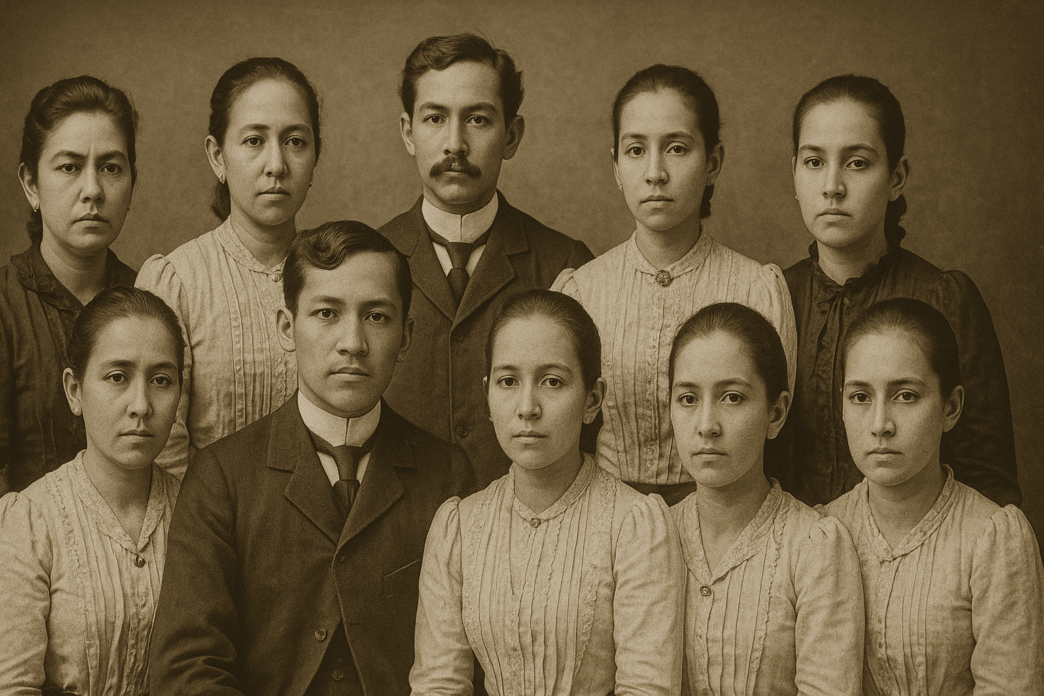

Jose Rizal was the seventh of eleven siblings whose lives shaped his moral convictions, supported his reformist mission, and preserved his legacy after death. Their sacrifices, challenges, and unity form one of the most remarkable family stories in Philippine history.

Introduction

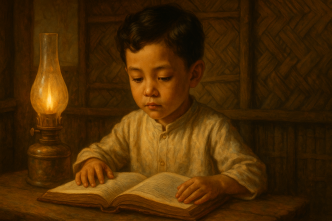

Jose Rizal’s life cannot be separated from the family that guided him. Born into a household of eleven children, he grew up in an environment defined by learning, discipline, and compassion.

The Mercado-Rizal siblings came into the world in this order: Saturnina, Paciano, Narcisa, Olimpia, Lucia, Maria, Jose, Concepcion, Josefa, Trinidad, and Soledad.

Each sibling influenced Jose in a different way. Some shaped his early years, others supported his studies abroad, and many suffered directly from colonial retaliation because of their family name. When Rizal was executed in 1896, the siblings carried forward his legacy through quiet resilience and active participation in the Revolution.

Their stories reveal how a single family helped support the birth of a nation.

The Family Environment in Calamba

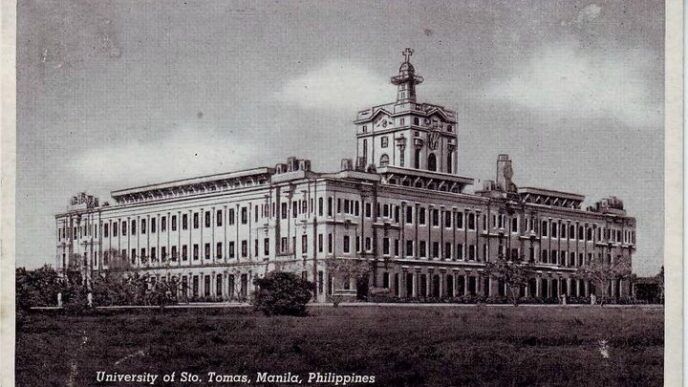

The Mercado-Rizal family home in Calamba was built on books, discipline, and shared responsibility. Francisco Mercado and Teodora Alonso raised their eleven children to value education, moral conduct, and awareness of injustice. The older siblings taught the younger ones, creating a household where learning was constant.

Yet Calamba was also the center of tension. During the 1880s, a land conflict erupted between the townspeople and the Dominican friars who claimed ownership of vast agricultural estates. The friars demanded rising rents and imposed harsh rules despite the tenants’ loyalty and improvements to the land.

Encouraged by Rizal’s writings and moral arguments, Calamba residents began organizing and documenting abuses. The friars retaliated by ordering mass evictions, confiscating property, and filing lawsuits. Homes, including those of the Rizal family, were destroyed. Siblings were interrogated, displaced, or threatened with imprisonment.

This experience forged in the children a deep emotional spine — a sense of justice, national dignity, and unity that would remain unbroken through the Revolution.

Saturnina (1st child): The Eldest Sister and Family Anchor

Saturnina, known as Neneng, carried the responsibilities of an eldest daughter with steadiness and grace. She helped raise her younger siblings, kept household matters organized, and ensured that José’s education abroad was financially supported.

Her husband, Manuel Hidalgo, became embroiled in the Propaganda Movement through his association with Rizal and was eventually imprisoned and exiled. Instead of retreating from the struggle, Saturnina stood by both her husband and her brother, aware that their sacrifices served a greater purpose.

After José’s death, she helped preserve the family’s letters, photographs, and documents. Her home became a center of memory where the siblings gathered to support one another through the Revolution, the Philippine-American War, and the early years of American rule.

Paciano (2nd): Mentor, Protector, and Later a Revolutionary General

Paciano influenced José more than any other sibling. Growing up under the moral brilliance of Father José Burgos, he witnessed the injustice of the Gomburza execution. This trauma shaped his political awareness and, through him, shaped José’s emerging worldview.

He protected José from early colonial surveillance, encouraged him to study in Europe, and managed the family’s finances and safety during the worsening Calamba conflict. His letters reveal wisdom, restraint, and deep affection.

After Rizal’s execution, Paciano joined the Revolution. He became a general under Emilio Aguinaldo, fighting in Laguna and contributing to military strategy. After the wars, he refused public office and lived quietly as a farmer, embodying humility after decades of sacrifice.

Narcisa (3rd): The Sister Who Preserved His Final Resting Place

Narcisa was artistically gifted, emotionally perceptive, and one of José’s closest sisters. She offered him support through care packages, letters, and visits.

When he was executed in December 1896, Narcisa searched tirelessly for his grave. She questioned cemetery workers, observed burial routines, and ultimately discovered the unmarked plot identified only by the reversed initials RPJ. She purchased the adjacent lot to protect it from tampering.

Her determination ensured that future generations could locate and honor José’s remains. Without Narcisa’s persistence, the hero’s resting place might have been lost.

Olimpia (4th): A Life of Quiet Suffering and an Early, Painful Loss

Olimpia lived a quieter life than her more politically involved siblings. She married Silvestre Ubaldo, a telegraph operator who later faced persecution because of the family’s reformist connections.

Olimpia died in 1887 at around 31 to 32 years old. Historical records do not document her exact cause of death. Most scholars agree she died suddenly, possibly from postpartum complications or a rapid illness, both common in the nineteenth century. Her death deeply affected the family, especially José.

Although she did not live long enough to witness the Revolution or José’s exile years, the hardships she endured — and the sorrow her passing caused — became part of the emotional landscape that shaped Rizal’s later writings.

Lucia (5th): Loyal Companion and Witness to Persecution

Lucia suffered one of the family’s most humiliating experiences when her husband, Matriano Herbosa, was denied Christian burial because of his supposed sympathy for José. The cruelty of this act revealed how far the colonial authorities would go to intimidate the Rizals.

When José was exiled in Dapitan, Lucia traveled with other family members to stay with him. She supported him through household management, companionship, and quiet encouragement.

After his death, she remained outspoken about injustices and lent assistance to revolutionaries who sought shelter or guidance.

Maria (6th): Josè’s Confidante and Emotional Counselor

Maria was calm, perceptive, and widely admired for her emotional intelligence. She was one of José’s most trusted confidantes, offering him guidance on personal matters, including his relationship with Leonor Rivera. Her advice reflected maturity and deep understanding of her brother’s heart and ambitions.

During the Calamba dispute, she helped maintain family stability amid lawsuits and displacement. After José’s execution, she preserved his letters and family memories, becoming an important source of historical information for later biographers.

José (7th): The National Hero

José Rizal stood at the center of the siblings’ shared sacrifices. His achievements were, in many ways, made possible by the love, mentorship, and protection of his sisters and brothers. His mission was their mission, and his suffering became their own.

Concepcion (8th): The Childhood Loss That Shaped Rizal’s Sensitivity

Concepcion, affectionately called Concha, was born in 1862 and died in 1865 at the age of three. Family accounts say she died from a sudden childhood illness, likely a fever, which was common in nineteenth-century Laguna.

Her death was one of the earliest emotional shocks of José’s life. He wrote later that he loved her deeply and felt her loss profoundly. This early experience with grief shaped the tenderness and empathy that would later define his writings.

Josefa (9th): Brave, Independent, and Loyal to the Cause

Josefa grew into one of the most politically active siblings. She joined the Katipunan and took on a role in revolutionary circles. She remained unmarried and devoted her life to principles of justice, freedom, and national dignity.

After José’s death, she continued participating in meetings and safeguarding his belongings, including letters and personal effects.

Trinidad (10th): Keeper of Mi Último Adiós

Trinidad played a decisive role in preserving José’s final message to the Filipino people. When she visited him in his cell, José whispered a code: “There is something inside.” She understood immediately. Hidden in the alcohol stove was his farewell poem, now known as Mi Último Adiós.

She protected the stove and the poem from the authorities and later revealed it at the right moment.

Trinidad remained one of the guardians of the Rizal family archive, preserving letters, artifacts, and testimonies that helped shape national memory.

Soledad (11th): The Youngest Sister With a Clear Voice

Soledad, the youngest sibling, grew up influenced by the family’s shared mission. She became a teacher and married Pantaleon Quintero. Her letters reflect a sharp mind and a strong sense of justice. She defended her family during political conflicts and helped keep their memories alive through careful preservation and storytelling.

How the Rizal Siblings Strengthened the Hero’s Mission

The eleven siblings formed a network of love, sacrifice, and shared responsibility. Their birth order created a natural structure of mentorship and support. The older ones guided José, the middle ones walked alongside him, and the youngest looked up to him and later carried forward his ideals.

They endured persecution during the Calamba dispute, supported José through his studies and exile, and protected his writings when the colonial authorities sought to suppress them. After his execution, they became custodians of his memory and contributors to the broader revolutionary struggle.

The story of the Rizal siblings is a story of ordinary individuals rising to the demands of an extraordinary period in Philippine history. Their unity strengthened the mission of a hero and, ultimately, helped inspire a nation.

To read Rizal’s full life story, see Jose Rizal: A Complete Biography.

Hi I’ve read a book about Jose Rizal and it was stated that his sister’s called him ute or moy, I would like to know if it’s true since I have never heard that nickname before aside from “Pepe”.