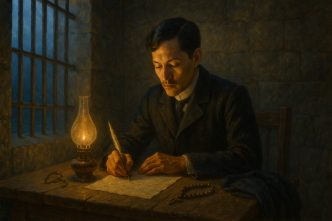

Rizal was exiled to Dapitan in July 1892 after Spanish authorities accused him of spreading “subversive” ideas and linked him to the newly formed La Liga Filipina. Governor-General Eulogio Despujol’s published decree cited “defamatory” leaflets (Pobres Frailes) allegedly found in his family’s luggage and passages from El Filibusterismo that, in the government’s view, favored separation from Spain. He was shipped south on July 15 and arrived in Dapitan on July 17, 1892.

Key dates at a glance

- July 3, 1892: Rizal founds La Liga Filipina in Manila.

- July 7, 1892: Despujol’s decree of banishment (citing Pobres Frailes and Fili).

- July 17, 1892: Arrival in Dapitan (7:00 p.m.).

- 1895: Linao waterworks inaugurated; Talisay dam operating.

- June 1896: Valenzuela consults Rizal; Rizal counsels caution.

- July 31, 1896: Leaves Dapitan with students under authorization to serve in Cuba.

Why Dapitan?

The political trigger

Rizal had just returned from Hong Kong and, on July 3, 1892, organized La Liga Filipina, a civic reform league. Within days he was arrested; the authorities treated his organizing, writings, and prestige as a threat and opted to neutralize him by deportation rather than open trial. Britannica’s summary is direct: he founded a non-violent reform society and was deported to Dapitan, a remote town in northwest Mindanao.

The legal pretext

The Despujol decree (published July 7, 1892) explicitly mentioned the discovery of handbills titled Pobres Frailes and pointed to El Filibusterismo’s dedication to Gomburza and an epigraph the regime read as advocating separation. The National Historical Commission of the Philippines (NHCP) preserves the text and Rizal’s own recollection of the encounter in Malacañang that led to his confinement in Fort Santiago and banishment “to one of the islands in the South.”

Arrival

Rizal left Manila on the steamer Cebú and set foot in Dapitan at 7:00 p.m. on July 17, 1892, where he was turned over to Commandant Ricardo Carnicero and initially lodged at the Casa Real.

What Rizal did in Dapitan (1892–1896)

Rizal refused to let exile be idle time. He transformed Dapitan into a laboratory of healing, teaching, engineering, science, and community enterprise.

Physician of the poor

He resumed ophthalmology and general medical practice, charging foreigners according to means and treating townspeople for free—a routine noted in a medical history of Rizal. He also maintained a small clinic near his home site in Talisay.

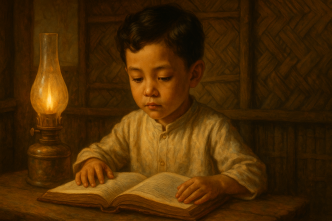

Teacher and school-builder

Rizal opened a community school for boys (“Los Chicos de Rizal”), where he taught academics and crafts with home-made teaching aids, maps, and natural specimens. The NHCP describes his hands-on method and how classes met in his house and in a hilltop kiosko he built.

Engineer and civic improver

He designed two waterworks that changed everyday life for the locals:

- Linao waterworks (town fountain with a sculpted lion-head spout), inaugurated in 1895;

- Talisay waterworks (dam and aqueduct) that still leaves visible traces at today’s shrine.

NHCP’s technical write-up documents the remains of the clay pipes, the reservoir, and the dam; another NHCP page adds that Rizal set up street lighting around the Dapitan plaza.

Naturalist and scientific collaborator

Rizal collected and shipped specimens to European colleagues, notably Dr. Adolph B. Meyer in Dresden, Germany. Several species gathered in Dapitan were named in Rizal’s honor, including Draco rizali (flying lizard), Rhacophorus rizali (tree frog), and Apogonia rizali (beetle).

Farmer and entrepreneur

He invested in land and organized livelihoods: developing a farm (later marked as the Katipunan, Zamboanga del Norte property) and forming an association of abaca planters/harvesters; he even explored improving local fisheries with a Spanish partner. These activities are detailed in NHCP’s “Rizal as a Farmer.”

He also won a share of the Manila lottery’s second prize (Ticket 9736) in September 1892 with Commandant Carnicero and Francisco Equílori/Equilor—money he plowed into land and projects. Contemporary reporting and historians have long noted his ₱6,200 share.

Public counsel, not insurrection

When Pío Valenzuela visited in June 1896 seeking his approval for an uprising, Rizal opposed a premature revolt and urged preparation (arms, elite support) first — an episode summarized by NHCP.

Personal life

In 1895, Josephine Bracken arrived with her adoptive father seeking eye treatment; she and Rizal became partners while in Dapitan. (Their relationship and later disputed marriage hours before Rizal’s execution are treated by standard references.)

The end of exile

In July 1896, Governor-General Ramón Blanco authorized Rizal to serve as a physician in Cuba. On July 31, 1896, he left Dapitan with several students, effectively closing his four-year exile. An NHCP article on his students records the date and circumstance of his departure.

Why Dapitan matters

Rizal’s exile shows his method of nation-building from below: elevate public health, democratize education, modernize infrastructure, professionalize agriculture, and cultivate civic character — without the instruments of state power. It is not the story of a silenced writer; it’s the story of a community made stronger by a deportado.