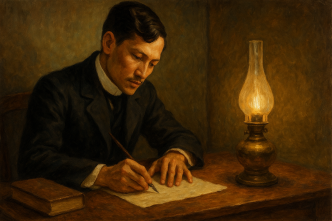

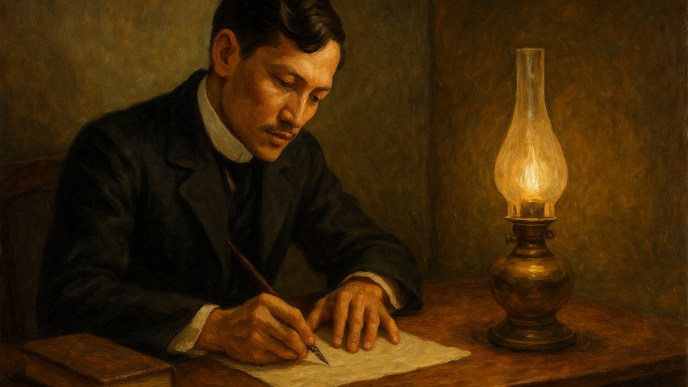

La Liga Filipina (“The Philippine League”) was a civic, reform-minded association founded by José Rizal on July 3, 1892 in the house of Doroteo Ongjunco on Ilaya Street, Tondo, Manila. Its goal was to organize Filipinos into a disciplined, mutually supportive body that would press for peaceful reforms — education, legal protection, economic uplift, and representation — within the Spanish colonial system.

Spanish authorities treated the new league as a threat; Rizal was arrested within days and banished to Dapitan, disrupting the Liga but not the movement it set in motion.

Why Rizal created the Liga

By 1892, the overseas Propaganda Movement (and its paper La Solidaridad) had popularized reform ideas, but it was distant from the daily struggles in the archipelago. Rizal envisioned La Liga as a grass-roots counterpart that would involve ordinary citizens directly in legal, educational, and economic initiatives—reform from below, not revolt. La Liga was a modest, loyalist reform society, yet colonial officials overreacted and crushed it early — ironically helping radicalize the movement that followed.

Aims and program

Rizal’s constitution for La Liga Filipina set five headline aims:

- Unite the archipelago into one compact, vigorous, homogeneous body.

- Mutual protection in times of need.

- Defense against violence and injustice.

- Encourage instruction, agriculture, and commerce.

- Study and apply reforms.

How it would work. The Liga had a tiered structure — a Supreme Council (national), Provincial Councils, and Popular Councils (town level) — to coordinate action. Members paid monthly dues (10 centavos), building a fund for scholarships, legal aid, small-capital loans, and cooperatives — practical steps to strengthen communities while pressing for systemic change.

Officers, members, and early growth

At the inaugural meeting, officers elected were Ambrosio Salvador (president), Agustín de la Rosa (fiscal), Bonifacio Arevalo (treasurer), and Deodato Arellano (secretary); Rizal served as adviser. Among members (and later reorganizers) were Domingo Franco and Andrés Bonifacio—names that would loom large in the next phase of the struggle.

Suppression, reorganization, and the decisive split

- Crackdown (July 6–7, 1892). Authorities arrested Rizal and deported him, paralyzing the newborn Liga.

- Reorganization. Within months, Domingo Franco and Andrés Bonifacio revived the Liga and channeled funds and support to La Solidaridad while recruiting councils in Manila and nearby provinces.

- Two paths emerge. As tensions sharpened, Liga ranks divided:

- the Cuerpo de Compromisarios (reformists) kept financing the Propaganda Movement;

- the revolutionists, led by Bonifacio and others, founded the Katipunan — a secret association committed to independence by force.

Key consequence

The Katipunan’s generally accepted founding date — July 7, 1892, days after Rizal’s arrest — shows how La Liga’s failure under repression catalyzed the transition from reform to revolution.

What La Liga Filipina did for the Philippines

Built a template for modern civic organizing

The Liga combined mutual-aid finance (dues, welfare funds) with legal-reform advocacy and education, anticipating the DNA of later Filipino civic groups, cooperatives, and NGOs: concrete help today, institution-building for tomorrow. Its constitution hard-wired community funds for scholarships, legal defense, and small enterprises — practical nation-building under colonial constraint.

Connected the reform press to people on the ground

By reorganizing to support La Solidaridad and deputations to the Spanish Cortes, Liga councils created a domestic pipeline of funds and recruits for the reform campaign, translating editorial ideals into local organizing.

Trained the cadre that would lead the revolution

Liga meetings cultivated discipline, secrecy, and networks later used by Katipunan organizers; many early Katipuneros (including Bonifacio) had been Liga members. When peaceful reform was blocked, those skills migrated into the revolutionary underground.

Clarified strategic choices for the nationalist movement

The Liga’s fate clarified the limits of loyalist reform in a repressive colony. The Compromisarios kept lawful agitation alive; the Katipunan embraced armed struggle. That strategic bifurcation, born from the Liga’s experience, shaped the Philippine Revolution’s leadership and timeline.

A short timeline

- July 3, 1892: La Liga Filipina founded (Ilaya, Tondo; house of Doroteo Ongjunco).

- July 6–7, 1892: Rizal arrested and deported; Liga activity stalls.

- Late 1892–1893: Liga reorganized under Domingo Franco and Andrés Bonifacio; begins funding La Solidaridad.

- July 7, 1892: Katipunan founded in Manila; many founders had ties to the Liga.

Bottom line

La Liga Filipina lasted only briefly in its original form, but its ideas, networks, and methods outlived the crackdown. It taught Filipinos to organize, to pool resources for the common good, and to press for rights through institutions—and when that path was sealed, it helped seed the revolution that would redefine the nation.

In that sense, the Liga is both the last chapter of peaceful reform and the prologue to Philippine independence.